A 21st-century Production of Antigone in the Bronx

by Brian Leahy Doyle

Department of Journalism, Communication and Theatre

From March 9-14, 2004, the Lehman College Theatre Program presented Sophocles' Antigone, directed by Professor Susan Watson Turner, in the Lovinger Theatre. Adapted from a translation by Mark Falstein, Lehman College's production of Antigone featured a cast of students and alumni in an innovative, contemporized production of this classic tragedy. In this article, I will discuss how in her interpretation of Antigone Watson Turner made Sophocles' fifth-century BC tragedy accessible to a twenty-first century Bronx audience.

While researching this paper, I observed Watson Turner's Antigone rehearsals, recorded my observations and also wrote a study guide for local high school audiences, posted on our department's web page and including an interview with the director. As I prepared this article for publication, I identified the key elements of her directorial concept: a reshaping of the play's choral and narrative elements; an emphasis upon such kinesthetic elements as music, sound, choreography and costuming; and an onstage enactment of the traditional offstage violence by utilizing contemporary set and lighting design choices.

I also explored reviews of other New York City productions of Antigone in order to place Watson Turner’s production in a wider context vis-à-vis trends in contemporary performance of ancient drama. Every year, it seems, Antigone graces a New York stage, and, as Margo Jefferson commented in her review of the May 2004 production at La MaMa, “It is considered de rigueur now for writers and directors to play freely with the classics.” (Jefferson 2004, E3) This certainly applies to Antigone, for reviews of the following productions suggest this directorial experimentation often leads to mixed results. For instance, director Richard S. Bach, in his New York International Fringe Festival production of Antigone Through Time, set the play “not in ancient Greece… but in the 1940s on a Greek island, where some 3,000 women have been placed in an internment camp.” (Gates 1998, B15) The women, part of the Resistance to the German occupation of Greece, have refused to sign a declaration of repentance and early in the play are shot by a firing squad, only to transform into characters in Sophocles’ Antigone. In the Women’s Project’s Antigone Project, five female writers and five female directors deconstructed Sophocles’ play, offering a “Rashomon-ized view of (Antigone’s) tragic plight.” (Hoban 2004, E5) While the production was engaging and funny, for the New York Times reviewer at least, the “snappy deconstructionist approach to the classic’s central themes ends up diluting them; it is a seductive dim sum rather than a satisfying meal.” (Bruckner 1995, 19)

Pearl Theatre Company artistic director Shepard Sobel’s November 1995 Antigone substituted Eurydice for the chorus: “since there is no one for Creon to argue with about his ideas of strong kingly government,” D. J. R. Bruckner observed, “he can only address the audience directly, and the running commentary of Eurydice-as-chorus begins to sound like a string of asides, not a warning that his confidence and stubbornness will bring disaster.” (Bruckner 1995, 19) Finally, in the National Asian American Theater Company’s production of Antigone in July 2004, director Jean Randich cast Mia Katigbak, the company’s producing director, in the role of Creon. Reviewing this production of Antigone for the New York Times , Bruckner observed that “whenever Ms. Katigbak is on a stage she owns it, and she makes a formidable male ruler who inherits not only a throne, but authority over the violent, bloodied and doomed remnants of the family Oedipus left behind.” (Bruckner 2004, E27)

In comparison, Watson Turner approached Antigone as an examination of the role of leadership in an authoritarian society, a compelling theme for Americans in the 2004 presidential election year. The following statement encapsulated her directorial approach: “When leaders act contrary to conscience, we must act contrary to leaders.” I reproduce here a substantial quotation from my interview with her in February 2004:

The inequities we watch today (via TV, newspapers and the Internet) are in some cases parallel to the actions of Creon. What do we do as individuals—as citizens, as artists, as teachers—to encourage action against what we know and understand to be unjust behavior?

My own response to being assigned to direct Antigone was not unlike a contemporary student's reaction to Greek drama. As much as I love directing for the theatre, the thought of preparing Antigone for contemporary artists and audiences presented a new challenge for me as a director. How could I adapt this centuries-old tragedy to ring true and make it provocative for a contemporary audience and examine the role of leadership in American society?

In my preproduction research I found that Antigone has been interpreted and approached from several different perspectives, and I read many different translations. The most interesting translation surfaced through an audio reading adapted by Michael Falstein. Falstein's adaptation geared the reader/listener toward a more ancient aural appreciation of the play.

This audio version used a narrator to bridge the gaps in the story, provided references for Greek language and Greek mythology, and, through these elements, unfolded the story more clearly and powerfully. My task as director then became one of translating the excitement and enthusiasm I felt by listening to this audio recording to the stage. By infusing the choral odes with dance my objective was to provide the audience with a visualization of Sophocles’ intention. (Watson Turner, 2004a)

Taking her cue from Falstein's adaptation, Watson Turner reshaped the traditional narrative and choral elements of Antigone. This included introducing the “Storyteller,” a role which set the production within a narrative and contextual framework for a contemporary audience. She also divided Sophocles' chorus into the King Creon Chorus and the People's Chorus, based upon economics, social status and physicality. Reflected in their body language, gesture, costuming and dramatic function, the King Creon Chorus was distinguished, learned, poised, and they reluctantly offered Creon advice, which he failed to heed. The People's Chorus, on the other hand, was more plebeian in their body language, behavior, costuming and dramatic function.

Throughout the production, Watson Turner mingled the People's Chorus with the audience in the auditorium, thereby establishing a connection between the spectators and the action of the play. As the People's Chorus observed the unfolding action, they pleaded with Creon on Antigone's behalf and encouraged the audience to join them. When the chorus moved onto the stage, the audience's energy and focus followed the chorus, disintegrating the “fourth wall” and engaging the audience to join the chorus to plead for Antigone's life.

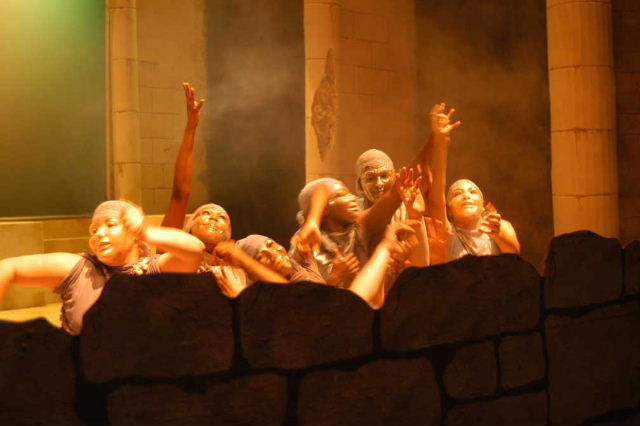

Watson Turner also reconstituted the play's choral-episodic structure, introducing choral dance sequences and enacting events normally narrated in the play's choral odes. For instance, Watson Turner introduced a dance sequence, a pre-parados before the prologos, which was underscored with composer Richard V. Turner's riveting score. This pre-parados featured the chorus members in identical translucent plastic masks rising up from the Lovinger Theatre's hydraulic orchestra pit in a haze of fog, presenting an image of Thebes as an uninhabitable land suffering from environmental abuse.

|

Plate 1 Members of the Chorus.

Photographed by Robert C. Roarty.

Later, as the Storyteller narrated the battle between Polynices and Eteocles, six actors with long wooden dowels enacted the battle in a stylized fight sequence choreographed by Dyane Harvey.

|

Plate 2 The Fight Scene.

Photographed by Robert C. Roarty.

At battle's end, both Polynices and Eteocles were killed, Polynices was rolled onto the orchestra pit, and Eteocles was lifted and carried off stage. The female chorus members sang and danced a hymn of praise to Dionysos in celebration of the victory. This dithyramb then segued into a “Dionysian ballet”, or victory celebration-dance, scored to a Latin-Caribbean tempo, culminating in a magic trick.

African, Latin and Caribbean rhythm influenced the musical score, along with such natural sounds as crashing waves, a receding tide, the calls of sea birds, thunder and lightning as well as plucked strings. Sound effects also shook the stage and toppled the elements in full surround sound. Susan Soetaert's costume design represented the lines and style of ancient Greek fashion with contemporary construction and fabric. The costumes, reflecting the director's concern with staying within the Greek frame, brought contemporary hints of fashion to the production's overall visual design and aided a twenty-first century audience's understanding of the play.

Richard Ellis' set design for Antigone employed architectural elements of the classical Greek theatre adapted to the Lovinger Theatre, a 500-seat proscenium theatre, with a steeply raked auditorium and stage-level vomitoria. Upon initial examination, the set resembled the skene of the ancient Greek theatre framed by columns at the curtain line rendered to show a structural decay echoing the decay in Creon's Thebes. While a significant portion of the action occurred on the Lovinger's forestage, action also occurred on a raised three-foot platform, reached by steps, which was bisected with a portal, in itself divided by the two columns. Sliding walls on wagons, resembling pinakes, were drawn on or offstage, creating either a solid wall or up to three upstage entrances. Upstage of the portal was another playing space that was separated from the downstage playing space by a black scrim.

In this upstage space, Watson Turner choreographed the deaths of Antigone, Haemon and Eurydice in slow motion suffused with blood-red light.

|

Plate 3 Antigone hanging.

Photographed by Robert C. Roarty.

Watson Turner commented on this obvious departure from staging traditional productions of Greek tragedy:

I elaborated upon Falstein's adaptation to portray Antigone's hanging, Haemon's suicide, as well as Eurydice's self-destruction, in order to tragically illustrate the consequences of Creon's abuse of power. By our illustrating rather than narrating these events on stage, we can force a contemporary audience to participate fully in and feel the tragedy. My goal was to have the audience members experience this pain and share in the responsibility. The chorus, by failing to speak out or by speaking out too late, was as guilty as Creon. (Watson Turner 2004a)

As Creon stood alone onstage, his hands dripping in blood, Lehman College's Antigone ended with Ken Ross's slide show presentation of photos of Hitler, Stalin, Idi Amin, Rafael Trujillo and Saddam Hussein, underscoring the link between these modern or contemporary authoritarian dictators and Creon himself.

Watson Turner accomplished a potent examination of the role of leadership in an authoritarian society. Lehman students who attended the production commented on the multiracial casting, the interaction between the chorus and the audience and the hard-hitting visual display of leaders gone astray. The most poignant comment provided by an audience member dealt with the clarity provided by this production to Sophocles’ story. Watson Turner, perhaps echoing her earlier observation about the chorus’s failure to speak out, remarked, “One patron, not a student, approached me to say that she understood now that silence is not always golden.” (Watson Turner 2004b)

References

Bruckner, D.J.R., 1995. Eurydice Replaces the Chorus, With Strange Consequences. New York Times, 11 November.

Bruckner, D.J.R., 1996. Escapades With a Hilarious Corpse. New York Times, 24 April.

Bruckner, D.J.R., 2004. Pity the Thebans, Your Friends and Neighbors. New York Times, 30 July.

Gates, A., 1998. In Resistance to the Nazis, Resonance With the Ancients. New York Times, 29 August.

Genzlinger, N., 2004. Sophocles Goes Truly Retro, Back to the Beginning of Time. New York Times, 20 May.

Hoban, P., 2004. Five Faces of Antigone, From Surfer Babe to Widow” New York Times , 27 October.

Holden, S., 1992. Antigone, With Clowns. New York Times , 16 February.

Jefferson, M., 2004. Look Out, Antigone, Creon Still Means What He Says. New York Times, 27 May.

Riding, A., 1999. Sophocles Gets a Twist in Paris, by Way of West Africa. New York Times , 8 June.

Watson Turner, S. 2004a Personal interview, 15 February 2004.

Watson Turner, S. 2004b Personal interview, 31 August 2004.

Weber, B., 2002. In the Beginning, Maybe, There Was Antigone. New York Times, 16 December.

Wolf, M., 2002. An Ancient Drama Whose Wisdom Is Always Modern. New York Times, 27 October.