POSTLUDE: STAGE SETTING AND SPACE

by Richard BeachamDepartment of Theatre Studies,

University of Warwick

Whatever the nature or the relationship between the frames involved, when acts of theatre are enacted, they do indeed take place, and the space is which this occurs provides its own differing types of frames, which can potently condition the manner in which we perceive and experience, for example, an ancient comedy. If we look at several of the possible venues, past or present, in which such works might have been performed, we can identify some of the ways in which this happens. Of course, this is a major topic in itself, and one which several of the papers given at this conference address, so I want here only to provide a brief overview, and some hypothetical computer based reconstructions.

|

This is an example of the stage sets depicted on numerous southern Italian vases. It depicts a very simple platform stage of the type which has been prevalent in theatre of every age.

|

This is a computer reconstruction of such a stage, drawing on the evidence of many vases that depict the basic architectural features of these very basic places for performance.

From such humble beginnings, the Greeks developed elaborate theatre architecture, which nevertheless preserved the fundamental elements of such early stage: a raised platform, with doors opening out on to it. The theatre of Epidaurus is the most famous surviving example of a Greek theatre.

Over the years, I had done a lot of work on reconstructing, hypothetically, Roman temporary stages from the evidence provided by Roman wall paintings. According to Vitruvius, the Romans had frequently used perspective painting - skenographia - to decorate the walls of their villas with the depiction of stage sets. Such painting both in technique and content had originated, as the name indicates, in the theatre. It is interesting to note in passing that in Roman times, therefore, theatre came into painting to change it fundamentally; while subsequently, in the Renaissance, painting returned the compliment, when it was (re-) introduced into the theatre and changed it, if not forever, at least for the next several centuries or so. This is an example of the type of continuous cultural exchange between theatre and other elements of society that I referred to earlier.

In looking at these paintings, one is struck how in a most literal sense, as part of their theatricality - one is tempted to say "their performance" -- they juxtapose different frames and present them to the spectator in a manner closely analogous to that I have been describing in regard to Plautine drama. We see a conflation and merging of "real" architecture (painted of course) with the "artificial" architecture depicted upon panels contained within the stage-like structures represented by the artists. The spectator stands within the actual space of the room on the walls of which these paintings have been executed, and with whose architecture the structures depicted in the paintings have a direct connection, extending and linking up to the architectonic elements of the room. Just like Plautine dramaturgy, the paintings thus function meta-theatricality, dissolving the illusion, even as they create it, and constantly engaging the viewer in their performance. Here are some examples:

|

A "skenographic" painting from the Villa of Fannius Synistor, now in the Naples Museum. The elaborate central doorway, and the masks suggest theatrical influence.

|

A painting from the Villa of Oplontis, near Pompeii uses skenographic technique to display architectonic and scenic elements in a manner which, according to Vitruvius, these were depicted in decorated stage sets of the period.

|

The House of the Vetii at Pompeii has a painting that strongly suggests the structure of a temporary stage, with a central doorway or aedicule, and two flanking doorways with figures descending steps.

|

The same pattern appears in a painting from the Room of the Masks, found in the House of Augustus at Rome. The artist appears to have depicted quite realistically, the structural and decorative elements of a temporary stage set. I used this painting to create a hypothetical "model" Roman temporary stage, and presented Roman comedies upon it. A detailed account of this work is in my book, The Roman Theatre and Its Audience, (Harvard 1991).

|

Using 3D computer modelling, it is possible to "extract" the structural elements depicted by the ancient painter.

|

|

I next created a more detailed computer model of the structure depicted in the wall painting.

|

Actors on the stage based on the Room of the Masks Painting, in a production of Plautus at the University of Warwick.

|

A structure similar to that shown in the Room of the Masks is depicted in a painting from the Villa of Oplontis.

|

A "extraction" of the structure depicted in the Oplontis painting.

|

The stage set based upon my research (and closely modelled upon the painting from Oplontis) which was constructed at the J. Paul Getty Museum. (Accounts and reviews of this project were published in Didaskalia, Volume 2 Issue 3, and Volume 1 Issue 5.)

The stage set suggested by the paintings, strongly suggests, or indeed imposes, a particular "style" upon the presentations taking place upon it. I have attempted to define and explore this style in the course of several years of practical experiment in producing plays upon such replica stages. In the process, I re-cycled my sense of this performance style back into the translations I've prepared: in effect then, wall painting was used as an aide to translation.

The stage's colour, architectural exuberance, and non-illusionistic "presentational" format, condition and control both the type of performance which could be accommodated upon it, as well as the manner in which the spectator is likely to "frame" and experience such performance. The stage is non-fictive in the sense that it does not attempt to represent through scenery any sort of narrative environment imitating the "reality" of the places in the story world enacted by the plays.

Thus in performance, the stage is itself a theatrical sign representing an ancient stage in Rome, while also existing as a pragmatic place for the performance to occur. The stage helps to set up both an immediate "aesthetic" experience through artifice, and simultaneously a "real" reflective experience, because it is so obviously presenting itself as an "artificial" historical artefact. Before one attempts however, too confidently to assert that the temporary stage set posited upon the evidence of the wall paintings, can provide conclusive evidence for an acting and performance style, it is prudent and sobering to remind ourselves that, according to the evidence of Cicero and Horace, in the late Republic and during the age of Augustus, Plautus continued to be performed, and if so, may in this period have been presented upon a significantly different type of stage. I will therefore conclude this "postlude" with some examples of a permanent Roman theatre.

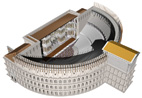

These are some views of a VR reconstruction based on my current research in collaboration with Professor James Packer in the Pompey Project, an extensive programme of archaeological investigation and analysis of the remains of the Theatre of Pompey the Great. These views from the computer model created by John Burge, show what with growing confidence we can suggest the stage of Rome's first permanent theatre, built in 55 BC, may have looked like. With a stage almost 300 feet wide, any actor, apart from having to pack a lunch, would clearly have to employ a style of performance radically different from that used on the temporary stages where Plautus was first performed.

|

The Theatre of Pompey was probably the largest Roman theatre ever constructed. Its stage was almost 100 metres wide, and the auditorium may have held as many as 30,000 spectators.

|

The auditorium (cavea) was crowned by a Temple dedicated by Pompey to Venus Victrix.

|

|

|

Computer reconstructions of the cavea, stage façade (scaenae frons), and stage of Pompey's Theatre.

Richard Beacham

University of Warwick