The Women from Trachis

by Sophokles

Translated and directed by Doron Bloomfield

March 29–31, 2012

Walgreen Drama Center, Studio One at the University of Michigan

Review by Amy Pistone

University of Michigan

The challenge of directing a Greek tragedy lies in telling an old story in a new way. Often this involves a new setting for the play or a distinctive translation. Doron Bloomfield’s recent production of Women from Trachis offered his own unique look at Sophokles’ Trachiniae. This performance was Bloomfield’s Senior Directing Thesis at the University of Michigan, and it combined a traditional performance of the play with an unconventional approach to the work. His program notes encapsulate this approach: “The elders feel emotions they know how to control, while the young are tossed about by the force of their deepest feelings. Because youth is unbridled, and maturity brings control, focus, wisdom, strength, and ultimately death. So no one wants to grow up.” Bloomfield, who served as both translator and director for the production, consistently emphasized this motif of generational conflict, drawing attention to the contrast between the young and the old.

In general, Bloomfield’s translation is well done and close to the original. He leaves some of the text in Greek, which works beautifully within the play. Deianeira is often addressed as despoina Deianeira, and characters often interject short Greek phrases (though I suspect that the frequent use of oimoi may not convey a sense of lament and despair to an audience unfamiliar with the language). The most striking use of Greek was in the chorus’s enthusiastic reaction to the Messenger’s announcement that Herakles is returning home; a long passage of Greek, delivered in the manner of a prayer, launches the women into a thoroughly festive scene, complete with trumpets and dancing. The ritualized rejoicing is interrupted by the silent figure of Iole coming onto the stage, bound as a prisoner of war. The juxtaposition was highlighted by the music and dance, and the overall effect was striking.

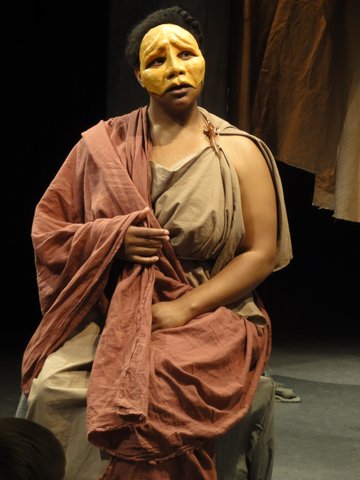

The performance combined masked and unmasked actors. All those who played two roles wore a mask for at least one of them, and usually for both. These were half-masks that covered the eyes and much of the face but left the mouth exposed. Perhaps significantly, the younger generation (Hyllus and the chorus) was never masked, creating a further aesthetic distinction between the two groups. Beyond masks, the costuming was very traditional, consisting of a variety of robes and similar garments. The set was minimalist but effective. A wall of the house could be lit to be transparent, allowing the audience to see Deianeira’s activities within. The theater was relatively small and the audience was seated very close to the stage. This intimacy was used to full effect by the actors, most notably Jeffrey Freelon as Hyllus, who ended the play with a speech delivered close to the audience, reproaching the gods for leaving “pain for us and shame for them,” and lamenting to the audience that it is “men who have to walk into the ruins, the hardest walk of all.”

At the other end of the spectrum, the interaction between Lychas (Freelon again) and the Messenger (Elizabeth Raines, who also played the Nurse) was strongly reminiscent of Shakespeare in its comic effects. Messenger speeches are a difficult element of ancient tragedy to recast for the modern theater, and the combination of Greek and Shakespearean conventions was an innovative (if not particularly smooth) attempt to bridge that gap.

Τhere were some significant modifications to the text of the original play. After Iole’s identity has been revealed to Deianeira and her chorus women, the Chorus Leader (Teagan Rose) piercingly screams “Let him burn!” in anguish at Herakles’ betrayal, a line that hangs in the air ominously for anyone in the audience who knows how the play ends.1 Later in the play, once Herakles is enmeshed in the poisoned robe and Deianeira has left the stage to kill herself, the two main chorus girls begin to argue. The secondary chorus member (Ellie Todd) seems to assign blame to Rose, as though her prophetic cry set the events in motion.

This curious issue of the guilt of the chorus, found nowhere in Sophokles, contributes to Bloomfield’s emphasis on the general motif of age. His vision is shown not merely in the aforementioned translation but also in a variety of other directorial choices. The chorus is composed of three young girls, and until the tragic events begin to unfold, they are shown playing games, reenacting the fight between Herakles and Achelous (a pantomimed wrestling match, narrated by a play-by-play commentator, with Achelous in the form of a bull), and braiding one another’s hair. Even as the events get significantly darker, the girls still bicker among themselves about the quality of Todd’s trumpet playing. They come across very clearly as young, in stark contrast to Deianeira’s more matronly aspect and the Nurse’s visible old age and infirmity. Similarly, Hyllus opens the play as an almost petulant young man. His interactions with Deianeira are those of any teenage boy with his mother. He seems vaguely annoyed or uninterested, but does agree to go in search of Herakles. Here again, his conduct highlights the contrast between the older generation (Deianeira, Herakles, and the Nurse) and the younger generation (Hyllus and the chorus). While this juxtaposition draws out an interesting theme, and Bloomfield deftly manipulates the story to place more focus on the contrast, the play itself resists the attempt.

The most obvious instance of this resistance is the character of Deianeira. Her decision to use the “love charm” on Heracles is motivated by her distress in the face of a younger rival (Iole). However, Deianeira does not act perceptibly old (as does the Nurse). She only seems old when compared with the overly young chorus that accompanies her. To fit into this broad motif of age, Deianeira needs to be identified with the “elders” in the play, but her words and demeanor do not suggest that she is elderly. This incongruity is surely due to the plot and text of the play, rather than the acting, which was exceptional. Deianeira was played by Melissa Golliday, who turned in particularly stunning performances as both Deianeira and Herakles. As Deianeira, she made her emotions and misfortunes the crux of the play. For modern audiences, the expectations of a woman in Ancient Greece can be somewhat distasteful, and Clytemnestra’s anger and desire for revenge can seem a more acceptable response than Deianeira’s commitment to make things work with Heracles and Iole. But Golliday’s Deianeira was convincing and sympathetic, particularly when she expressed her hatred for the sort of women who would take vengeance on their husbands, even as her own unwitting vengeance was unfolding. Both of her roles were masked, and she was extremely adept at conveying strong emotion through the mask, using her eyes poignantly.

Ultimately, the production combined traditional elements (a script that largely follows the Greek, traditional costumes, and so on) with an innovative approach to the play. Bloomfield’s attempt to find and illuminate a thread of generational conflict within the work is unique and admirable, and his directorial choices creatively advance this theme, though Deianeira’s role complicates the opposition of old and young that he wishes to establish. Bloomfield and all his actors surely deserve credit for offering a variation on this classic work of Sophokles, and while some of their choices are not entirely effective, the undertaking was inventive and thoroughly enjoyable.

note

1 The Greek here reads ὄλοιντο μή τι πάντες οἱ κακοί, τὰ δὲ / λαθραῖ’ ὅς άσκεῖ μὴ πρέπονθ’ αὑτῷ κακά (334–5), which still conveys a hostile reaction toward Herakles, but does not directly foreshadow (and, in the minds of the chorus, cause) his fiery death.