Medea, Written in Rage

Starring François Testory

Written by Jean-René Lemoine

Translated and directed by Neil Bartlett

Live music by Phil Von

Theatre Royal, Brighton, May 26th 2018

Peter Olive

Royal Holloway, University of London

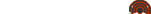

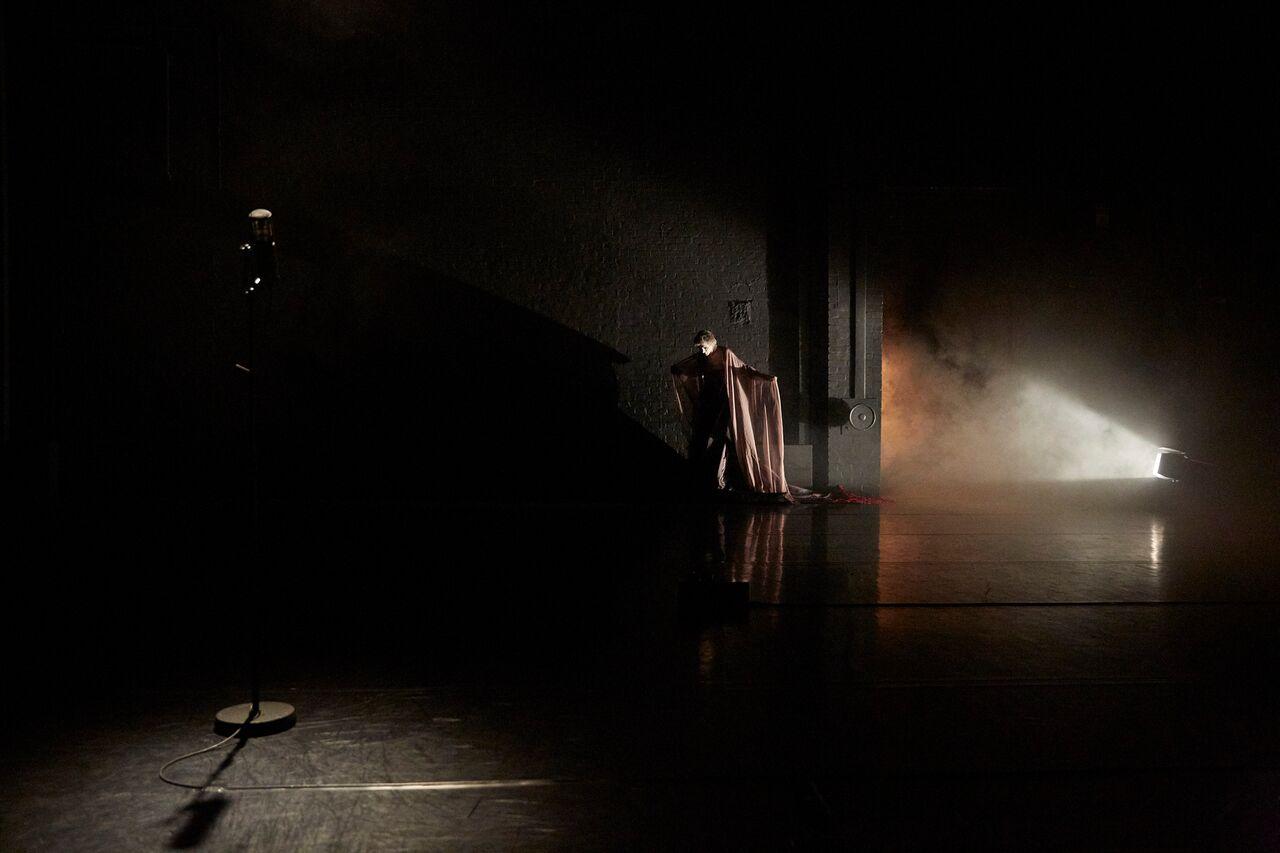

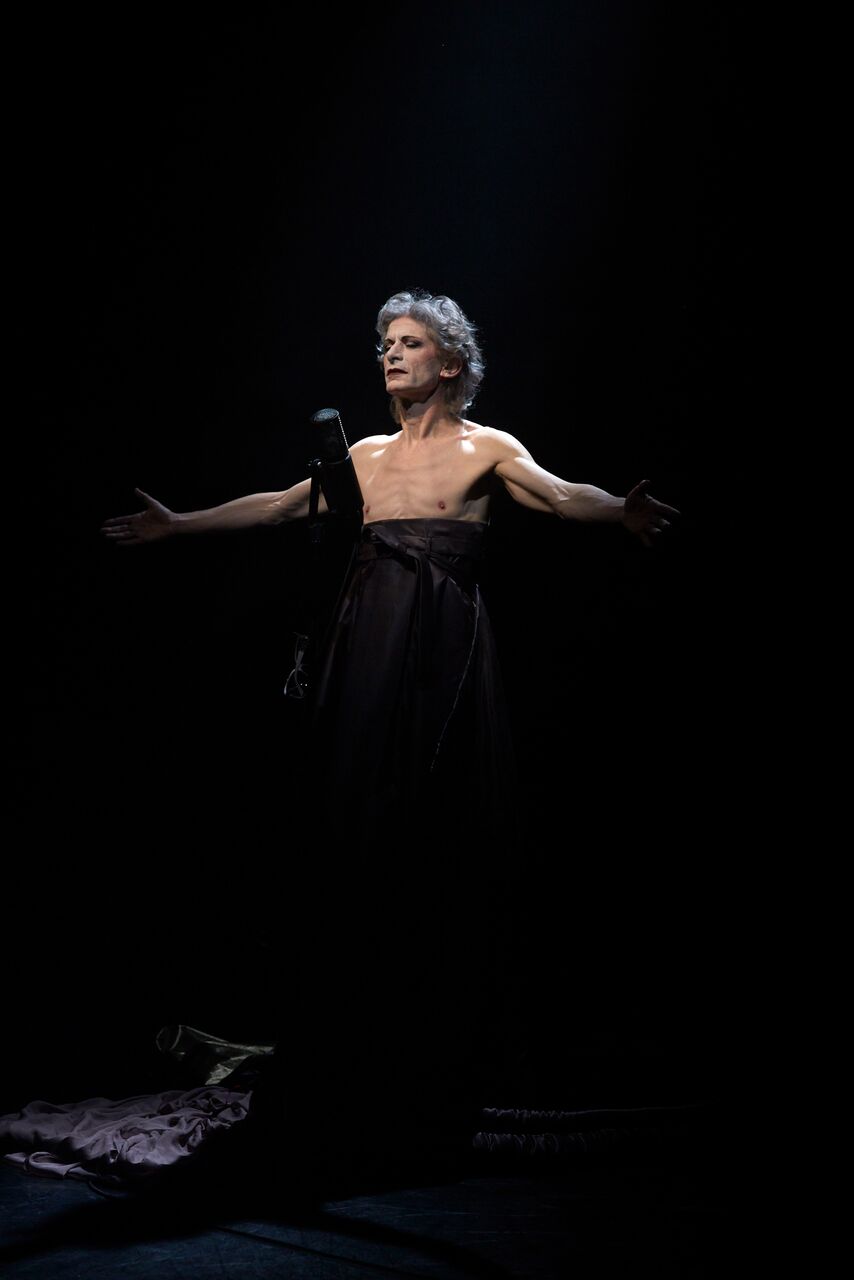

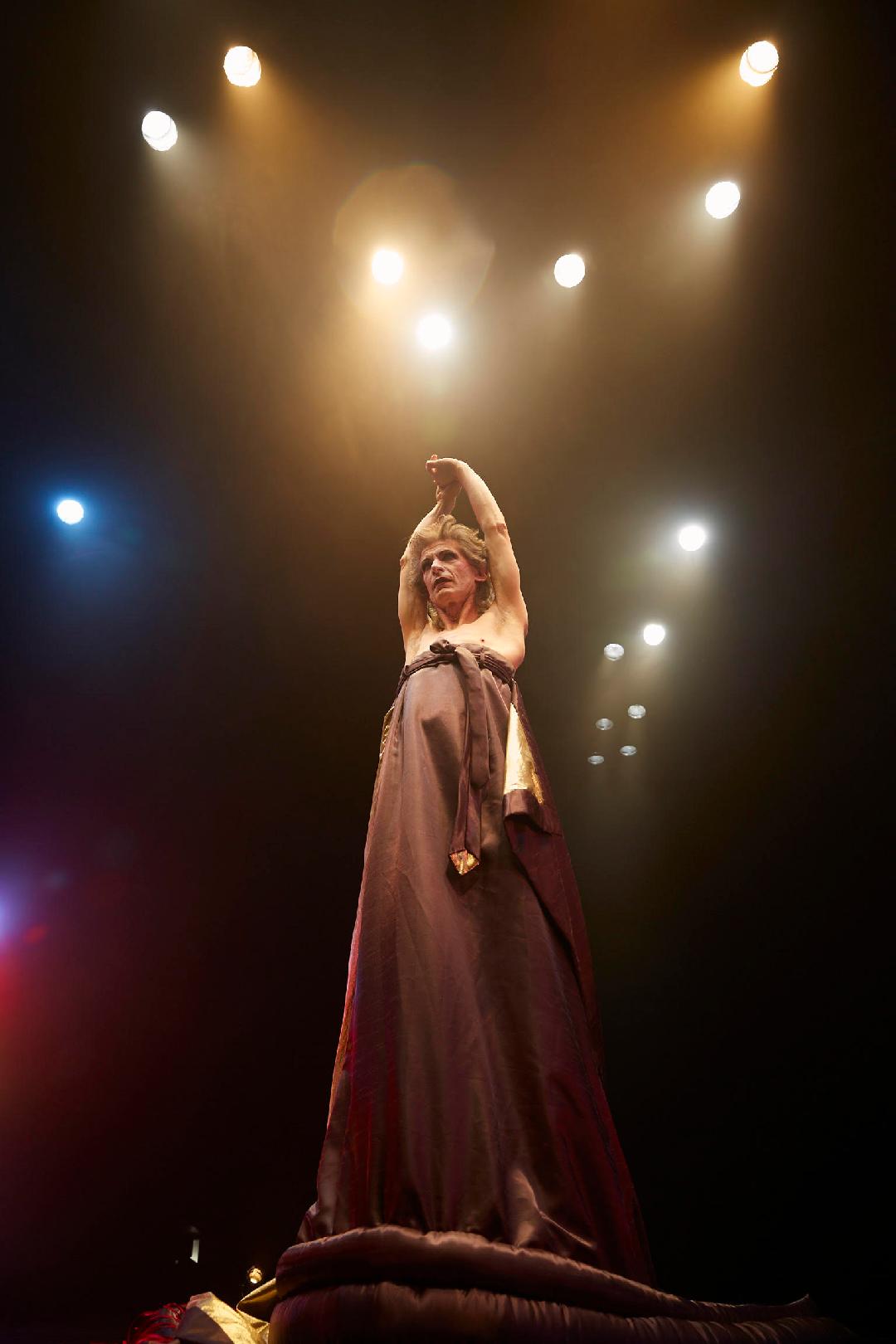

Photo: Manuel Vason | ||

Photo: Manuel Vason |

Photo: Manuel Vason |

Photo: Manuel Vason |

Photo: Manuel Vason |

Photo: Manuel Vason |

Photo: Manuel Vason |

Photo: Manuel Vason |

Photo: Manuel Vason |

|

Gender-blind casting serves as a reminder of how recently women have been permitted to perform their own sex. People with an interest in classical reception might have all kinds of preconceptions about a one-man production of Medea: there is an established tradition of cross-dressed Medeas, and as gender comes to be defined in ever-broader terms, there is little danger that this aspect of performance will decline in interest. But while publicity shots of Medea, Written in Rage give the impression of a cabaret act in drag, that is as far as such a similarity goes: this production is the first English-language version of Jean-René Lemoine’s self-performed and critically acclaimed Medée, poème enragé (debuted 2014 at Maison de la culture de Seine-Saint-Denis, Bobigny, and revived and toured in 2015–16). Lemoine, a Haitian-born actor and playwright resident in France, has had an illustrious career as an actor, director and writer. His earlier work includes Iphigénie, a version of Iphigenia at Aulis which was awarded the Émile Augier prize by the Académie française. A cursory google of Iphigénie suggests an author intently engaged with the tradition of Greek tragedy in reception. My expectations were high, and were not disappointed.

The set consists of little more than the microphone stand at which Medea tells her story. The moment she sweeps onstage, we are gripped by her self-assurance and star quality. Testory (a dancer by training) moves with the grace and ease of Hollywood royalty to the red carpet, decked out in a bespoke gown by Mr Pearl, couturier to the A-list. Immediately the space is hers, and from the outset, we are addressed as Medea’s friends. She beams as she introduces herself. With the girlish grin of an excitable teenager, she lifts her gown to reveal her shoes, apparently a nod to the elevated status (and footwear) of tragedy: she is raised upon eight-inch, box-like stilts. Like the tragic cothurnus or pattens of medieval Venice, they give her a larger-than-life stature that becomes Medea’s otherworldly grandeur: she is aloof and aloft throughout.

Medea begins her story in the manner of Euripides’ “Women of Corinth” speech, careful to outline her situation and secure our pathos early on. What follows is not, however, a line-by-line translation of Euripides, but a free creative adaptation. At Medea’s instruction, the story “rewinds” farther than most dramatic versions: “Stop!”, “Rewind!”, “No, further back!”, she barks at musician Phil Von, the only other presence onstage, who obediently provides the sound of a tape rewinding. (He stands to one side throughout, a presence only when spoken to; himself all but invisible, he and a laptop provide the soundtrack to Medea’s life story, with everything from sound effects to lush orchestral mood music.) Medea now dwells extensively on the antecedents to the myth. We are taken to her bedroom in Colchis, where, without warning, what appears to be a humdrum domestic scene between two teenaged siblings quickly takes a turn for the outlandish. Absyrtos is no sooner introduced than graphically described ejaculating down Medea’s throat. (We later learn that she has convinced her nervous younger brother to let her fellate him.) Sex-scene monologues are confidingly purred like vivid erotic fiction, sparing no explicit sensual detail; by the time she tells us of Jason’s arrival, we are sensitised to the terrifying power of Medea’s sexuality.

The heroine is in no hurry to advance her story to the day on which Euripides’ play is set. She takes the time to afford an elaborate characterisation to minor characters like the daughters of Pelias, mentioned only in passing by Euripides. The breadth of vision and virtuoso range of her monologue is breathtaking, including all manner of topographic and cinematic detail. Medea describes at turns snippets of overheard conversation between her father and Jason; a glimpse of her father in pursuit, pacing the bridge of his ship on the horizon; the seating plan of a banquet at King Pelias’ court; the sound of her children calling her through her kitchen window in Corinth. Sound design and music by Phil Von works just as hard, transporting us from the creaking lower decks of the Argo to the modish beats of uber-chic, poolside entertainments laid on by Creon for Jason, Corinth’s newest celebrity. As the music accelerates to pounding dance beats, we sense an uncomfortable change of mood. Our narrator tells us how the parties descended into late-night debauchery, wearily describing her uncomfortable involvement in Jason’s increasingly intimate “bromance” with Creon—three-way sex, and not exactly consensual, judging by her matter-of-fact account of it. Amid this confusion, another bombshell is casually dropped: Jason would like to sleep with other girls and other boys. We sense a tremor in our hitherto unflappable narrator, as she quotes her attempt to sound casual in reply. The direct speech of this and other encounters is given prominence by vocal transformers on Von’s laptop, enabling Medea to quote characters’ words through her microphone with the distortions of memory electronically reified. Most of the male characters come out like science-fiction villains, while the women have a breathy, pipsqueak quality to them. This fits well with the interiority of the telling: we hear characters as Medea remembers them.

One of the play’s most daring and successful revisions of Euripides is an inversion to the order of the killings: Medea kills her children before she visits Creusa with poisoned vestments. Rather than an escalation of vengeance, the killing of her rival feels far more gratuitous, confirmed by a chuckle. (This Medea can make homicide seem alarmingly personable.) Like the dismembering of Absyrtos earlier in the play, the details of the filicide itself are narrated with detached indifference. There follows the Nurse’s response and the arrival of Jason, ever slow on the uptake, who tells Medea that he fears reprisals, and that she must wake up the boys.

The decision to pare down Medea to one character takes theatrical mimesis a step closer to diegesis, and the script seems well aware of the potential for first-person multiplicity. The narrator-protagonist writes and rewrites her own story on the fly, reporting and disowning competing accounts of her own destiny, even invoking her own mythological comparanda: “Iseult, Brunhild, Penthésilée!” she exclaims intermittently, as if name-checking her role models. We get a close glimpse at our heroine’s power to dissemble and pretend, the interior monologue giving the sense of a candid backstage interview as Medea psyches up to perform. While she talks us through her makeup routines and continually restyles her gown, we empathize with her tedium: she is word perfect in the role of trophy wife while her heedless husband sleeps around. The voices of the supporting cast become nothing but background noise, as we see and hear through Medea’s senses: we too chuckle at the gormless daughters of Pelias with their little gasps about their father’s wrinkles, and roll our eyes at the slow-witted Jason. With no chorus to bring us to our senses, we find ourselves drawn into Medea’s psychopathy, led unchallenged like tourists in her amoral universe, fearing for her as she describes herself almost drowning in the act of drowning her sons. The filicide is magnificently unrepentant.

Lemoine’s Médée, poème enragé made liberal use of code-switching from French into English and Italian, a detail preserved in Bartlett’s translation. A recurrent feature in Medea’s performance history (for which, see e.g. Macintosh, Kenward and Wrobel [63]), the code-switching is far more than a token reminder of Medea’s status as a foreigner. This linguistic phenomenon is said to happen for five reasons: the inadvertent tendency to revert to a mother tongue at moments of high emotion, the urge to fit in to a community, the need to get something done, to convey a thought precisely, to say something in secret… All seem quite apposite for Greek tragedy’s most famous barbarian. In exploiting this feature, Lemoine was not afraid to show off his erudition, alluding to another grand dame of the continental stage: Medea is equipped with a triumphant refrain, preserved verbatim by Bartlett, “Muori, dannato!” seemingly a quotation from the vaunt of Puccini’s Tosca over the body of her perfidious nemesis, Scarpia. Directors faced with learned borrowings like these might fear the risk of seeming esoteric, but in performance the gleeful sadism of these lines’ delivery only adds to Medea’s secretism. Nor does the production privilege high culture over pop culture: lyrics from the Moody Blues’ 1967 love song Nights in White Satin form another refrain. In this context, these quotations strengthen the impression of an introspective mind, self-absorbed and above obligation to explain itself.

Medea’s status as a foreigner is given careful attention. More explicitly than in any other production I have seen, we are continually reminded that Medea is an outsider. Calling to mind Pasolini’s 1969 film of Medea, the unusual topography of Medea’s home is given extensive description; where other productions preserve generalities about barbarians from literal translations of Euripides, or leave audiences to notice subtleties of production design that suggest that Medea is an outsider, this play’s script (both Lemoine’s original and Bartlett’s translation) spells out the agony of Medea’s acculturation, giving vivid examples: Medea spits as she lists all that she did to assimilate to Jason’s culture, telling us how she gouged out her tattoos and wrenched out her nose rings, changing her dress for something “Western”. Not without precedent in recent receptions of tragedy, Medea, Written in Rage reinvents the barbarian by introducing an incest element that has no ancient source. Graphic descriptions of sex with her brother are interspersed with tender portraits of sibling affection, making this curious feature as compelling as it is repulsive. Gender does not seem to be of primary concern: Testory’s masculinity is undisguised, and the temptation to refocus attention on the gender conflict of Euripides’ play has been resisted. (Lemoine has said he would be pleased to see the role reprised by either a man or a woman.) Instead, our attention is squarely focused on Medea’s status as an outsider, an immigrant and an exile who has been hugely underestimated. More than anything, Testory’s Medea is a chameleon, a testament to the resourcefulness of a human being under pressure.

In an interview, Lemoine has cited Heiner Müller’s and Pasolini’s versions of Medea as influences. Like these, his version of the story is a consummate reworking of Euripides’ play that at the same time shows reverence for Greek convention: rendering the entirety of the action as one character’s recollection and eye-witness account makes the performance feel like a 90-minute messenger speech, expertly delivered in the finest tradition of the ancients. Part of the play’s success is its conscious engagement with the theatrical history of the Medea story, a tradition in which this masterly production merits recognition. Bartlett, Testory and Von have effected a very sensitive version of Lemoine’s play, and I hope my reader will not have to wait long for a revival.

References

Macintosh, F., C. Kenward, and T. Wrobel. 2018. Medea: a Performance History

http://www.apgrd.ox.ac.uk/learning/medea-a-performance-history.