Prometheus Bound

translated by Nicholas Rudall

Directed by Terry McCabe

April 27-June 10, 2018

City Lit Theater

Chicago, Illinois

Reviewed by Allannah Karas

Valparaiso University

Given the static situation of the Promethus and a predominantly divine cast of characters, Aeschylus' Prometheus Bound poses a significant challenge for modern theater performance. Yet under the artistic direction of Terry McCabe, the City Lit Theater company creatively surmounts these obstacles with the art of puppetry and the use of a lucid (world-premiere) translation by Nicholas Rudall. Through these means, City Lit lends Prometheus Bound an attractive conceptual coherence around the central question of individual and collective agency under the tyranny of Zeus.

City Lit prides itself on being a theater which "communicates a commitment to specific civilizing influences - tradition imaginatively explored, a life of the mind, [and] trust in an audience's intelligence."1 From the very beginning of Prometheus Bound, City Lit's puppets (designed by VonOrthal Puppers) loom large in the small black-box theater, and the clear delivery of Rudall's translation, coupled with dramatic background music (world-premiere musical score by Kingsly Day), immediately invites the audience into the story of the freethinking Titan god and the cuases of his unjust punishment. An explanatory background prologue weaves throughout the opening dialogue between two of three larger-than-life puppets representing Hephaestus, Power, and Brute Force. These impressive figures fasten Prometheus to his rocky crag (a slightly raised scaffolding platform designed by Jeremy Hollis).

Power, with a scarred lightning-bolt aspect; Brute Force, a silent, smoldering volcanic figure; and reluctant Hephaestus, whose tuft of red hair and tremulous voice liken him more to a hesitant child than to the blacksmith of the Olympians.

"This is hard," Hephaestus whimpers. "I am his family. I am his friend."2 But the other lumbering marioneetes drown out Hephaestus' weak protests and Prometheus' faint groans. With loud hammer blows they affix the Titan offender (a live actor): hand, foot, and through the chest. Once they leave Prometheus alone on the stage, these giant charcters are never seen again. Despite their fierce aspects and more fearsome mission, they remain mere caricatures of their function: puppets with unnatrually long arms, extensions of the long arms of Zeus.

Throughout, director McCabe also highlights issues of agency and freedom by capitalizing on the artificial separation of the pupper characters from the voice(s) that speak(s) for them. For instance, a single male vocalist (Charles Schoenherr) skillfully speaks for and through the representations of Power, Hephaestus, and eventually Oceanus and Hermes, as if mediating the power of Zeus that, in a sense, ultimately animates them. The Oceanids, similarly, receive their speech from six women (Casey Daniel, Lara Hohner, Jenna Fawcett, Sahara Glasener-Boles, Krista Leland, Justine Raczy) who stand along a wall stage right throughout the play. Dressed in varying shades of blue, these choral voices chant, harmonize, wail, and question Prometheus. Meanwhile, black-draped puppeteers carry the images of the actual Oceanid spirits, "each corresponding to specific source of fresh water somewhere on the planet, represented here as drops of water of various sizes clinging to seedlings that have borne them on the wind."3

Their choral "voices" remain on the sidelines and rarely make eye contact with any character on stage. Instead, their ethereal, mobile-like puppets gently rattle and swoop and come close to Prometheus in tune with the emotional fluctuations of their vocal counterparts.

The characters of Prometheus and Io, interestingly, are the only non-puppets in the drama, the only characters possessing true agency. They are also the only characters who suffer directly at Zeus' hands. Yet the very contrast between these figures and the remaining cast of puppets highlights the central significance and hidden power of the bound god and the one who is destined, eventually, to deliver him.

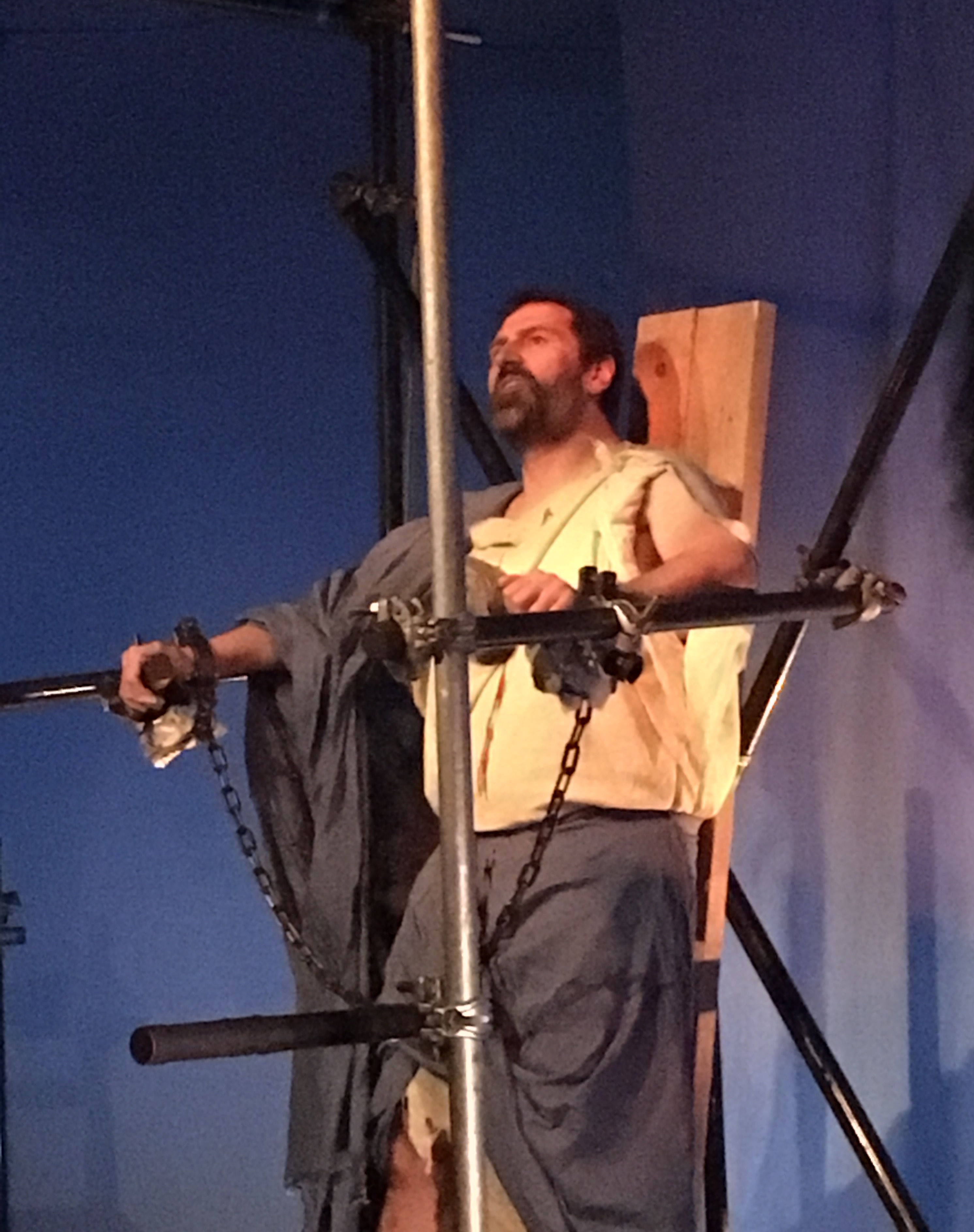

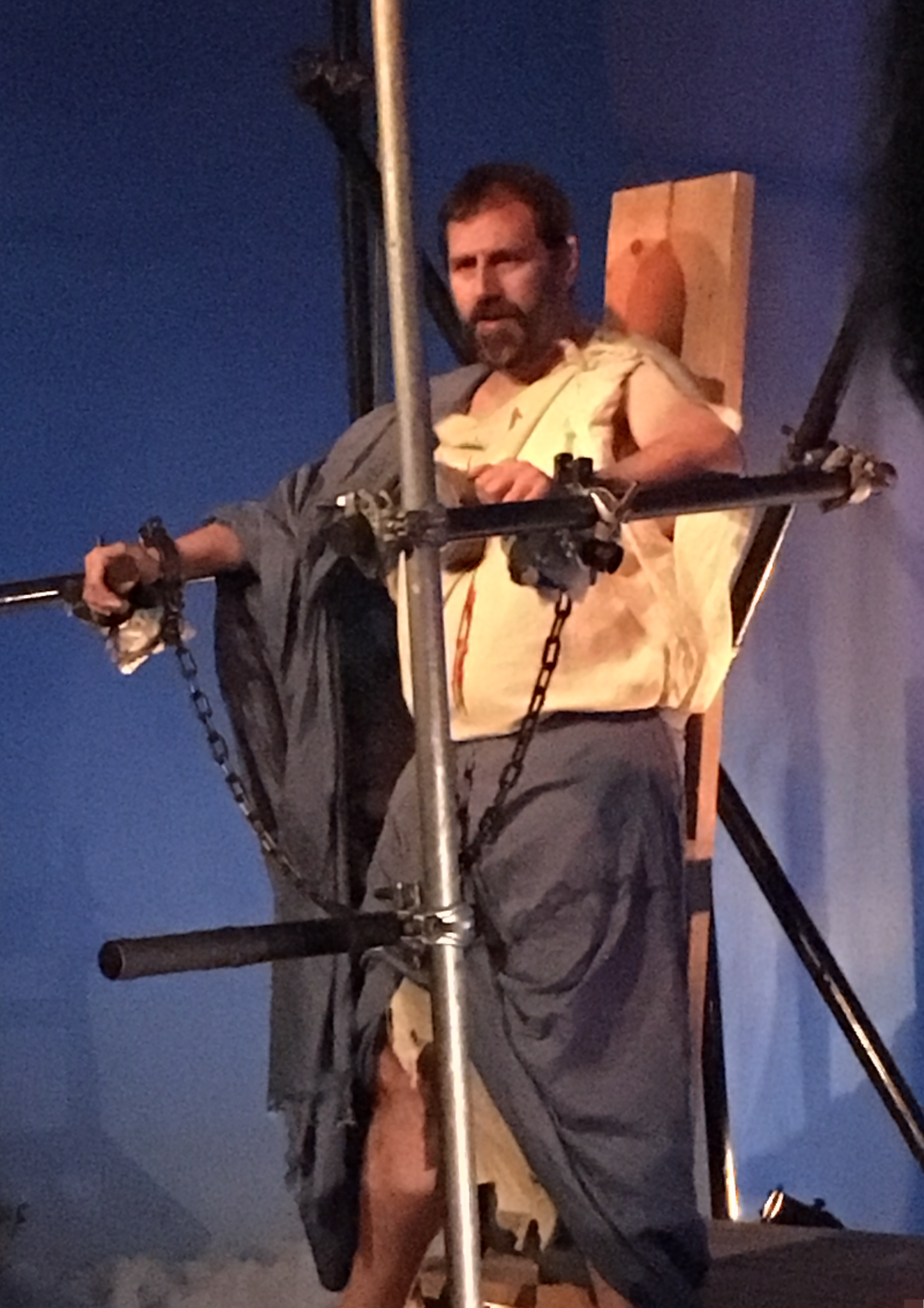

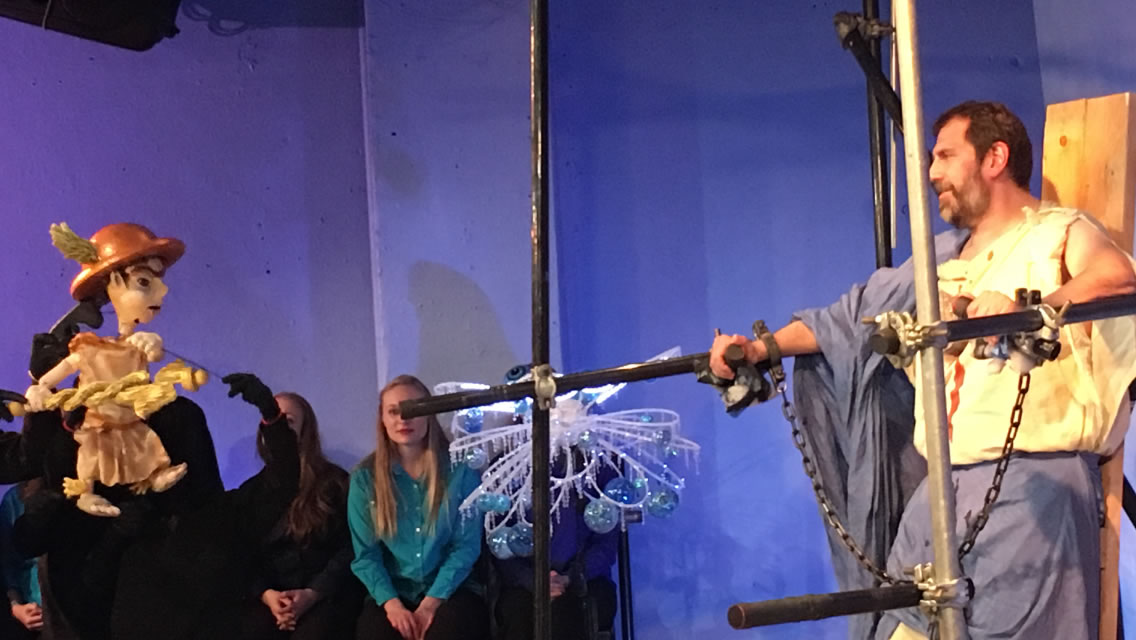

For example, rather than displaying a half-naked man writhing in pain,4 McCabe presents Prometheus as a fully clothed and sandaled figure in complete possession of his wits and of the situation. The live character of Prometheus (played by Mark Pracht), although chained to a scaffolding-like structure with a wedge driven through his chest, remains remarkably composed.

This Prometheus holds himself aloof from every puppet and even from Zeus himself. With a superiority complex and sense of humor born of forethought, he continually intersperses explicit condemnation of Zeus and scathing sarcasm throughout his dialogue with the puppets that approach him.

Prometheus' self-possession emerges with particular clarity by contrast with Oceanus, a puppet the program describes as "the personifcation of the circular river that flows around the edges of the earth."5 Oceanus' disembodied, whiskered face floats atop a "hippocampus, a winged creature of the sea"6 that is, incidentally, more akin to a toy hobbyhorse than to a kingly steed.

Unbeknownst to his blustering self, Oceanus sets the audience's expectations of his character with an ironic remark addressed to Prometheus: "Despite your extraordinary vision / You do not understand / That people who talk too much / Usually get punished."7 Yet while the puppet reprimands the suffering Titan for his treacherous speech, he himself speaks far beyond what is useful. The cynical disdain of Prometheus' responses underlines the pathetic irony of this exchange and the empty garrulousness of Oceanus on his mock-majestic hippocampus.

Prometheus, however, emerges from this encounter and the next as consistently more knowledgeable, powerful and wise than the lesser deities who come to berate or, at best, to console. The weakness of the Oceanids, for example, provides a continual foil to Prometheus' strength. After their father's departure, they ask for further details of Prometheus' story, which he, in turn, expounds majestically. Composer Kingsly Day is perhaps at his best with the operatic choral questioning and background music that rises and falls to the pathos of Prometheus' narrative of goodwill towards humankind. Prometheus tells his tale in a full and powerful voice as a self-sacrificing, unconquerable divinity. At the same time, his earnest tone and the accompanying music draw deep compassion from the audience.

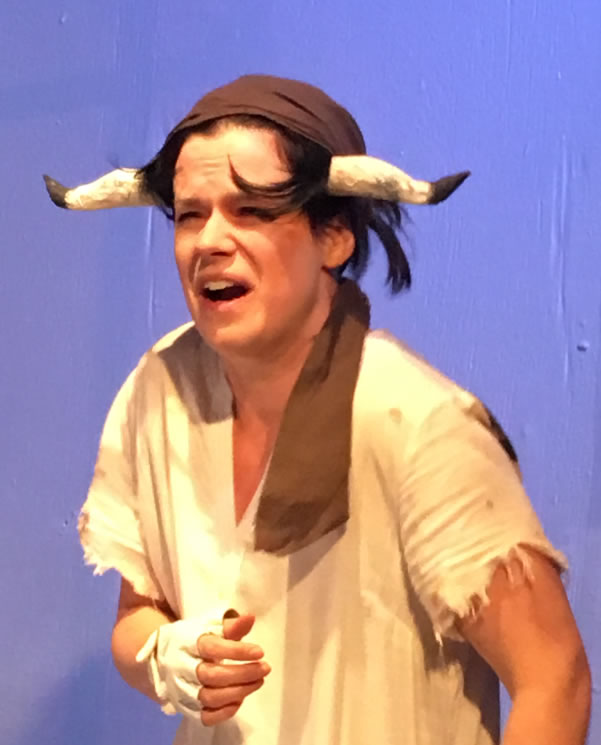

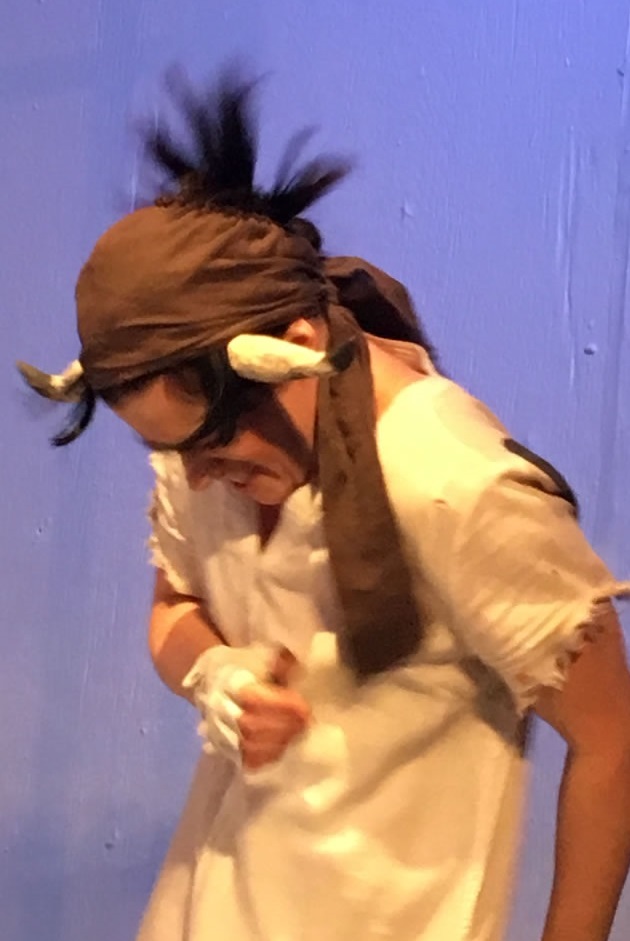

As the play unfolds, another non-puppet character enters on stage for the first time: Io (played by Kat Evans). The appearance of a second live actor invites a rich comparison between Io and Prometheus: both are victims of Zeus, and yet both are more alive, more whole, and freer than the rest of the cast. At the same time, however, the bersek and frantic cow figure of Io poses a perfect contrast to the noble, immobile Prometheus. While the august and solmn Titan stands affixed by chains for his benevolence, Io bolts back and forth across the stage, contorting jerkly in gadfly-induced madness, her punishment for "arousing" the desire of a lustful god.

With her erratic yelping, the constant swatting of her long cow tail (held in the hand of the actress), and her spasmodic leaps from center stage to the platform of Prometheus' crag, Io wears down the audience with her unnerving and continuous convulsions. In this way she practically forces from audience a distressed sense of pity towards her plight. Only Prometheus can provide some relief to the tormented cow-girl, by foretelling her future travels (which black-draped puppeteers trace out obligingly and humorously on a large map of the ancient world).

In the end, however, Io and Prometheus remain engulfed in pain and mutually dependent on each other for the end of their troubles. The promise of salvation hangs in the air, spoken but not yet fulfilled, as a hardly comforted Io skittishly exits from the stage.

It might seem by the end of the play that the puppet-agents of Zeus prevail. In the last scene, a minuscule, flying imp appears: the puppet of Hermes, who comes to pester Prometheus and threaten him with an ultimatum from Zeus. Hermes cuts a droll figure: flitting pompously through the air and jabbing his caduceus with comic impertinence to the rhythm of his saucy speech.

But Prometheus brushes him away like a bothersome insect. When Hermes grumbles: "You talk to me as if I was a child," Prometheus spits in his face and retorts, exasperated: "Well you are a child and as stupid as a child . . ."8 Hermes huffs offstage after this speech, while the long-suffering Prometheus awaits the inevitable. His craggy post shudders and shakes, thunder rumbles, lightning flashes. As part of the scaffolding falls in an "X" before his face, Prometheus is "submerged" beneath the earth.

In the end, however, the figure of Prometheus emerges from City Lit's performance as the truly free hero with a mysterious agency expressed through his prophetic voice and reinforced through his non-puppet status. The tragedy of the drama lies only in the present (although not ultimate) limitations of Prometheus' static state, as City Lit expresses so aptly in a prefatory line by Auden: "All I have is a voice to undo the folded lie."9

notes

1 City Lit Theater, Playbill for Aeschylus' Prometheus Bound (2018) 3.

2 The simple and accessible clarity of Rudall's translation comes through particularly in these lines from the Greek:τὸ συγγενές τοι δεινὸν ἥ θ᾽ ὁμιλία, which literally translates: "you know, family is a stragely dreadful, and also companionship" (Aesch. PB 39). This Greek is text taken from the Loeb Aeschylus edited by Herbert Weir Smyth. This and other translations in the notes are my own, unless otherwise stated.

3 City Lit Theater, Playbill for Aeschylus' Prometheus Bound (2018) 4.

4 Compare the image of Prometheus presented in 2013 Cambridge Greek Play production of Prometheus, presented at the Cambridge Arts Theatre, Cambridge, UK: http://cambridgegreekplay.com/.

5 City Lit Theater, Playbill for Aeschulus' Prometheus Bound (2018) 4.

6 Ibid.

7 Literally, the Greek, ἢ οὐκ οἶσθ᾽ ἀκριβῶς ὢν περισσόφρων ὅτι / γλώσσῃ ματαίᾳ ζημία προστρίβεται; (Aesch. PB 330-331), translates as follows: "Or, do you not know clearly, being beyond wise, that punishment is inflicted on the foolish tongue?" Once again, Rudall has succeeded in creating a clear and humorous rendition of the Greek for a modern audience.

8 The Greek has: Hermes: ἐκερτόμησας δῆθεν ὡς παῖδ᾽ ὄντα με. Prometheus: οὐ γὰρ σὺ παῖς τε κἄτι τοῦδ’ ἀνούστερος; (Aesch. PB 986-987).Rudall's translation is quite precise here, and by emphasizing the "are"in his delivery, Mark Pracht brings out the bitterness of Prometheus' exchange with the little lackey of Zeus.

9 From W. H. Auden's poem "September 1, 1939," cited by City Lit Theater, Playbill for Aeschylus' Prometheus Bound (2018) 2.