Euripides’ Iphigenia at Aulis

Directed by George Kovacs

January 30-31 and February 1-2, 2013

Nozhem First People's Performance Space, Gzowski College, University of Trent

February 9, 2013

George Ignatieff Theatre, Trinity College, University of Toronto

Review by Timothy Wutrich

Case Western Reserve University

The Classics Drama Group (CDG), founded in 1993 by Martin Boyne at Trent University, has presented an ancient Greek drama on campus every year since 1994. While Euripides has been a favorite with the company’s directors, 2013 marks the first time in the group’s twenty-year history that it has performed Euripides’ Iphigenia in Aulis. The CDG production of IA, therefore, provided a rare opportunity to see the play in North America. Notwithstanding a production in Estonia reviewed in the previous issue of Didaskalia, IA remains one of the lesser-seen Euripidean plays. In contrast, while productions of IA have been few, scholarship on the play has been constant. How fortunate, then, that the CDG production came to light through the efforts of a scholar-artist who is both an authority on the text of Euripides’ IA and who has sound credentials as a director and actor. George Kovacs, Assistant Professor of Ancient History and Classics at Trent University and Director of the CDG, offered Toronto theatergoers an artistically and intellectually engaging version of IA. Kovacs had written his doctoral thesis, Iphigenia at Aulis: Myth, Performance, and Reception, on IA; the CDG production permitted him to test his academic ideas in the theater. The opening scene between Agamemnon and his slave, the chariot entrance of Klytemnestra and her children, and the final Messenger scene describing the mysterious rescue of Iphigenia—passages of the play subjected to intense scholarly debate and frequently considered spurious—all appeared in this production. The result was an outstanding theatrical experience which gave spirited form to a late, problematic play by Euripides, whom Aristotle called “the most tragic of the poets.”1 Moreover, in a manner worthy of Euripides, the production, while offering an unequivocal interpretation of the play’s mysterious final scene, compelled the modern audience to reevaluate its own understanding of the Homeric heroic tradition.

TranslationMost North American productions of Greek tragedy are given in English translation. While modern, educated audiences are aware that the plays of Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides were written in ancient Greek, the myths and the characters that appear in them are generally familiar to North American theatergoers. Yet no successful director will choose a translation lightly. Writing about the use of modern translations for the stage in How to Stage Greek Tragedy Today, Simon Goldhill remarks that “the script and the style of performance are mutually implicative choices” and that “the first answer to ‘what is the best translation [i.e. of any given Greek tragedy]?’ must always be ‘for what type of performance?’”2 The modern critic of Greek tragedy in performance, therefore, ought to consider choice of translation together with other elements in evaluating a production.

Choices of translations abound even for a play which, like IA, is not often staged. Consider for a moment three commonly available poetic translations of IA. Even a cursory glance at a key speech in the play, Iphigenia’s proclamation of the necessity of her death (1395–1401), reveals how differently contemporary translators can render the same text, and how the choice of translation is a director’s first major artistic statement in a theatrical production. The Chicago series contains a translation of the complete text by Charles R. Walker. Walker’s version in free verse frequently approaches iambic pentameter and, according to the translator, was made as “an acting version in English for the modern stage.”3 Walker’s translation, although over fifty years old, has aged reasonably well and retains the form of a dramatic poem for the stage. Here is Walker’s version:

IPHIGENIA

O Mother, if Artemis

Wishes to take the life of my body,

Shall I, who am mortal, oppose

The divine will? No—that is unthinkable!

To Greece I give this body of mine.

Slay it in sacrifice and conquer Troy.

These things coming to pass, Mother, will be

A remembrance for you. They will be

My children, my marriage; through the years

My good name and my glory. It is

A right thing that Greeks rule barbarians,

Not barbarians Greeks.

It is right,

And why? They are bondsmen and slaves, and we,

Mother, are Greeks and are free.

(Charles R. Walker, 1394–1403)

Walker sticks reasonably close to the Greek, although he elaborates and adds to the text, making his lines weighty. His tone is not stiff, but it is formal, and he has his Iphigenia address the rhetorical question to her mother (μῆτερ not appearing in the original Greek question). Iphigenia will give her body to Greece (δίδωμι σῶμα τοὐμὸν Ἑλλάδι) and it will be a “remembrance” for her mother (the Greek has μνημεῖα, “monument”); the things Iphigenia does will serve as her children, her marriage, her good name, and her glory (καὶ παῖδες οὗτοι καὶ γάμοι καὶ δόξ᾽ ἐμή). Walker’s next sentence translates the Greek literally; then he adds a rhetorical question—“and why?”—not in the Greek. Walker’s final two lines in this passage translate βαρβάρων δ᾽ Ἕλληνας ἄρχειν εἰκός, ἀλλ᾽ οὐ βαρβάρους, / μῆτερ, Ἑλλήνων: τὸ μὲν γὰρ δοῦλον, οἳ δ᾽ ἐλεύθεροι, which might be literally rendered “It is right that Greeks rule Barbarians, but not, Mother, / that barbarians rule Greeks: For they are slaves, and these are free.” Here Walker expands the Greek, giving us two words to translate δοῦλον, one of them (“bondsmen”) rather archaic sounding.

Likewise Paul Roche set out to bring IA into English as a dramatic poem. In the introductory remarks on “The Challenge of Translating” in his volume Euripides: Ten Plays (1998), Roche states that his “principle of faithful re-creation (for re-creation it must be if it is to live) is that one language best translates another when it is least like it and most true to its own genius.”4 Roche also translates the received text with performance in mind. Here is Roche’s version of Iphigenia’s speech:

IPHIGENIA

If Artemis is determined to have my carcass

shall I a mortal female cheat the goddess?

No, I give my body to Hellas.

So sacrifice me and sack Troy.

That will be my memorial through the ages.

That will be my marriage, my children, my fame.

For the Greeks to govern barbarians is but natural,

and nowise, mother, for barbarians to govern Greeks.

They are born slaves. Greeks are born free.

(Paul Roche)

Roche’s translation moves more swiftly than Walker’s, yet lacks grandeur. Would a young girl really refer to her own body as a “carcass,” even if she imagined herself dead? Moreover, in the Greek Iphigenia does not entertain the possibility that she could “cheat” Artemis, but merely asks rhetorically whether she could get in the way (ἐμποδὼν γενήσομαι). Further, Iphigenia’s injunction to “Sacrifice me and sack Troy” has alliterative strength, but misses the righteous tone of a martyr who imagines conquering an enemy. Overall, Roche’s version is fast and forceful, but lacks the dignified tone one might expect from an exceptional young person convinced that she has a mission that is somehow greater than she.

Finally, IA appears in the volume Women on the Edge: Four Plays by Euripides translated by Mary-Kay Gamel. Gamel, like Walker and Roche, translates the received text. Then she writes “This is a prose translation, fairly literal, not intended for the stage; it follows the diction and word order of the original closely, with little attempt to evoke the poetic effects of the original.”5 Professor Gamel’s description of her translation seems surprisingly understated. Her prose approaches free verse and, while literal, sounds like idiomatic English, even powerful and poetic English at that. Finally, although Gamel claims that her version of IA was “not intended for the stage,” Kovacs selected it for the CDG production and it served the production well. Gamel translates the speech thus:

IPHIGENIA

If Artemis wishes to take my body,

will I, a mortal, stand in the way of a goddess?

No! Impossible! I give my body to Greece.

Make the sacrifice! Eradicate Troy! For a long time to

come

that will be my monument, my children, my marriage,

my fame!

It’s proper for Greeks to rule barbarians, Mother, not

barbarians Greeks,

because they are slaves, but Greeks are free!

(Mary Kay Gamel, 1395–1401)

Gamel’s version, like Walker’s, manages to capture the formal tone of the young martyr. At the same time, Gamel’s Iphigenia speaks simply and to the point. The result is a dignified idiomatic speech that sounds like something a real teenager might say to her mother in a moment of heightened emotion. With Goldhill’s above-cited remarks in mind, one could answer that Gamel’s translation was the right choice for this production.

Performance spaceOver its twenty-year history, the CDG has performed in various theaters, using The Pit at Lady Eaton College until 2005, when the company began to stage plays at Nozhem: First Peoples Performance Space in Gzowski College. The program notes explain that the CDG often takes its productions to other universities in Canada, including Trinity College in the University of Toronto, where I saw the road production of IA at the university’s George Ignatieff Theatre on a cold but sunny Saturday afternoon in February just after a major blizzard had hit the Eastern United States and Canada.

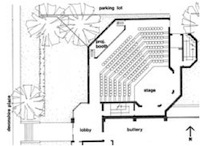

The George Ignatieff Theatre is a small university theater. The auditorium holds 180 spectators within its dark, wood-paneled walls. The plan of the auditorium reveals a fan-shaped, gently raked space, separated into three sections: a large central section flanked by two small side sections, each section divided by an aisle of 12 steps. The dark, wooden boards of the stage thrust out a few feet towards the audience on three sides. The stage is not deep, nor is it elevated more than a foot or so. Three shallow steps connect the stage directly to the floor of the auditorium. No orchestra pit or other area divides the stage from the audience: this theater offers an intimate environment. Three portals covered with black curtains form the stage’s back wall, yet they were not used for entrances or exits in this show. Instead, actors entered from behind dark-blue curtains, stage right and stage left. The stage was lit from lights hung directly over the small stage, while three further beams with lights illuminated the stage, one directly over the farthest downstage edge of the stage on all three sides, and two others facing the stage on all three sides of the thrust just over the first rows of audience seating. An aisle runs behind the back row of seats, separating the technical booth from the auditorium, and leading to exits right and left. The house right entrance was used during the show for the entrance of the chariot bearing Klytemnestra, Iphigenia, and Orestes.

The small scale of the George Ignatieff Theatre posed a potential problem for the CDG’s production of IA. Euripides’ play thrusts audiences into the middle of a stormy, early episode in the Trojan myth cycle and features prominently five major figures from Greek mythology: Agamemnon, Menelaos, Klytemnestra, Iphigenia, and Achilles. Such a play would seem to require a large space to hold such gigantic characters and such primal epic action as the preparation for human sacrifice before the Trojan War. On one hand, therefore, the production risked being cramped in a space better suited to the realistic domestic drama of Ibsen, Shaw, or Tennessee Williams. Yet on the other hand, seeing Euripides’ recasting of the larger-than-life Homeric characters on a small stage emphasizes a key point about the play: the Euripidean characters are fallible human beings in a domestic tragedy. The Homeric names and reputations do not change the fact that Euripides presents characters in a drama that could happen anywhere, anytime: a man plans to kill his daughter when he realizes that her death will advance his career; his wife discovers his scheme and burns with rage and resentment; a young idealist wants to do the right thing but is not quite sure what that is or how to do it; and an innocent young girl, full of love for her parents, makes an astonishingly brave decision when all the adults around her fail to do so. It is to the credit of Kovacs and the actors of the CDG that they made these large characters work in this small theater.

The actors and performanceJust before 3:00 p.m. the house opened for general seating. The sound of a solo acoustic guitar welcomed the audience into the theater. The music had a folksy, western, new-age sound, with arpeggios and chord progressions played softly and brightly in major keys. The sound was gentle, relaxed, and peaceful, not really the type of music one would associate with the tragic or the Greeks, but it was inviting. The audience began to filter into the space slowly and steadily for fifteen minutes. The audience was multi-generational, multi-racial, and international. About seventy people were in the audience when the house doors closed and the show began at 3:20 p.m.

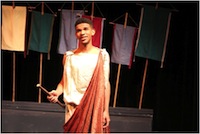

As the music continued, the soldiers (Lane McGarrity and Stephen Sanderson)6 and the Messengers (Nick Zawadzki and Kayla Reinhard) emerged from the wings in silence and began to set the stage. They erected a large white canvas tent center stage and then flanked the tent with a row of six colorful gonfalons placed in stands on each side of the stage. Agamemnon (Kevin Price) appeared onstage at this time, holding a gonfalon before planting it in the stage-left holder. As the music stopped, the Servant (Najma Aden-Ali) emerged and the play began. The text of IA begins with structural abnormalities: the opening lines appear in the anapestic meter, although one would expect iambic trimeter, and the prologue delivered by a single character, also expected in Euripides, is delayed.7 Kovacs staged the received text while making unexpected choices in other aspects of the production. For instance, he cast a short, dark-skinned woman dressed as a woman—Euripides’ text calls for an old man (ὁ πρεσβύτης)—as the Servant to play opposite the tall, light-skinned Agamemnon, thus accentuating differences between Agamemnon and his slave. The casting choice is not trivial and raises questions. Why would a woman servant be in the commander’s tent, if she were not a concubine? Shouldn’t her presence make Klytemnestra jealous, the Klytemnestra who ten years in the future will kill Cassandra partially out of jealousy? Moreover, should the racial contrast be a cue for the audience to be thinking about race relations at the beginning of the play? The production did not explore or resolve these questions.

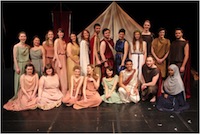

As Agamemnon sends the Servant to deliver a revised message to Klytemnestra and prevent her from coming to Aulis, the chorus of women from Chalkis appears. The CDG chorus featured eleven women (Mandy Novosedlik, Lindsay Cronkite, Emma Fair, Christine Gilbert-Harrison, Sadie McLean, Jenna Lawson, Grace MacDonald, Monika Trzeciakowski, Pippa O’Brien, Bingbin Cheng, and Kayla Reinhard). Dressed in a variety of solid-color tunics that ranged in tint from pistachio to dusty rose, from peach to beige, the chorus added color to the stage picture. Here the youthfulness of the student actors served the text perfectly. As the women of the chorus talked about the heroes gathered at Aulis, they recalled the young people of many periods preoccupied with the search for celebrities. They expressed enthusiastically their desire to see the great warriors and were absolutely giddy with the thought of “The one whose lightly running feet / go fast as wind – Achilles, son of Thetis, / Chiron’s pupil."8 When Menelaos (Nate Axcell) appeared on stage to confront Agamemnon about reversing his decision, the chorus divided and stood on each side of the tent, framing the stage picture and suggesting division visually while drawing focus to the debating brothers. The chorus moved elegantly, spoke clearly and beautifully, and in spite of the small space they had for movement, fit meaningfully in the action of the play. The fact that the chorus did not seem out of place in this late Euripidean play compels one to reexamine the conventional opinion that the chorus had become an embarrassment in late tragedy.9

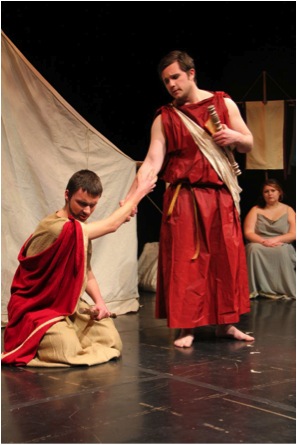

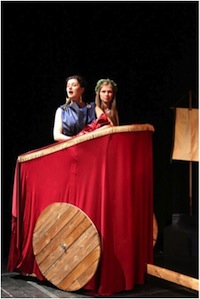

Kovacs succeeded in creating many memorable stage pictures. In the debate between Agamemnon and Menelaos, for example (334–401), Kovacs’s casting and costuming choices allowed for visual differences to underline the ideological differences between the two characters. The taller, thinner Agamemnon, clad in a beige tunic and red cape, scowled at his shorter, stouter brother, who wore a red tunic and a beige sash and pouted as his brother castigated him for wanting Helen back at any cost. The arrival of Messenger I (Nick Zawadzki) interrupted their debate with the announcement of the imminent arrival of Klytemnestra, Iphigenia, and Orestes, and a new stage picture emerged: the Messenger beaming with pride at bearing what he thought was good news and the Atreidae visibly disturbed by his message. After his speech, the picture changed again. Agamemnon fell to his knees, giving Menelaos the dominant stage position as he now towered above his brother and reached out to him with the words, “Brother, let me touch your right hand.”10 The arrival of Klytemnestra (Jocelyn Ruano) and Iphigenia (Anastasia Kaschenko), in a chariot pulled in through the house-right auditorium door by the Soldiers, created a stirring change in rhythm and provided the necessary spectacle, as the Chorus rushed offstage to meet them. In the ensuing scene, Jocelyn Ruano as Klytemnestra captured in an excellent manner the chatty excitement of a Greek matron preparing her daughter for marriage, while Anastasia Kashenko deftly played a young girl not quite sure what to expect.

The scene in which Agamemnon’s family arrived, however, posed the next potential problem for the actors, for this scene requires the representation of several different generations onstage simultaneously. For the crisis to develop in IA, a discernible age difference needs to be apparent between Iphigenia and her parents and, to a lesser degree, between the Old Servant and Klytemnestra. Iphigenia’s youthful innocence must contrast sharply with Agamemnon’s worldly experience. An audience needs to see a generation gap in order to grasp the horror of Agamemnon’s decision. How can this mature man send this young girl to her death? Later, when the Servant denounces Agamemnon to Klytemnestra, the Servant’s age and length of service are important factors. However, in spite of the high quality of the acting overall, it was difficult to suspend disbelief in regard to age distinctions in a production where the realistic mode predominated. Costumes, stage properties, and the set evoked antiquity. The actors’ diction was high without sounding unnatural or stagey. Movement flowed simply and naturally: there was no attempt at “ritualistic” or “stylized” gestures, and even dance-like moves made by the chorus seemed like the actions of young, impressionable women in love with the idea of foreign heroes. Yet, given the realistic mode of acting, nothing could hide the fact that Agamemnon and Iphigenia were too close in age to be father and daughter, and the “old” Servant and the royal couple she served were all about the same age.

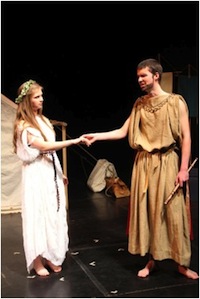

Nevertheless, in spite of this, the young actors did well in performing challenging roles. Jocelyn Ruano, in particular, deserves praise for finding the right tone and projecting the dignity, experience, pain, and general complexity of the Klytemnestra character. Indeed, her scene with Achilles (Gabriel Hudson) showcased her talent. We watched as Klytemnestra was transformed before us from a proud queen, happy to see the young man she imagined would be her son-in-law, to one embarrassed at her mistake, to one humbled and forced to beg as a suppliant on her knees in the hope of saving her daughter’s life. This Klytemnestra was aware of the irony in her situation and of the necessity of making the right moves to counter Agamemnon’s devious plans. In the scene in which she confronts Agamemnon regarding his true intentions, Ms. Ruano captured the stunned outrage of a betrayed wife, just as Mr. Price played well the defensive reaction of an Agamemnon who can only glare and make a high-sounding speech about his duty to the army and the force of divine will. After Agamemnon’s departure, Iphigenia was left to mourn her fate with her mother. Ms. Kaschenko’s delivery here seemed understated, but perhaps that was better than if she had taken it over the top in a scene that could so easily have erupted into hysteria. Achilles’ reappearance soon after made clear the futility and even absurdity of any rescue plan, as he related to Klytemnestra the desire of the Greeks for the sacrifice to proceed. At this juncture, Iphigenia has a difficult task to perform: to break an apparent stalemate and sacrifice herself, moving from dreading death to embracing it. The character transformation has bothered critics since Aristotle.11 Ms. Kaschenko pulled it off. Indeed, as she progressed in her long speech (1368–1401), she gained power and credibility, the otherworldliness of the character accentuated on stage by a bright white spotlight that engulfed her.

Earlier, I mentioned the textual problems in IA and how Kovacs dealt with those at the very beginning and about one-third into the play. The end of the manuscript is also in bad shape.12 Moreover, the denouement of the received text has rarely pleased scholars, critics, translators, readers, or directors. After Iphigenia’s final exit, the text as it stands introduces a Messenger (here Messenger II, played by Kayla Reinhard) who announces to Klytemnestra that the gods have rescued Iphigenia at the moment of sacrifice. Agamemnon reappears to tell his wife that she can rejoice now that their daughter is with the gods; he instructs her to go home, while he himself sails for Troy. Kovacs kept all of this material in the CDG production, a sound decision on two counts. First, in keeping the controversial ending, Kovacs let viewers decide whether the ending seems organic. His decision resembles the choices an editor of the Greek text or a modern translator needs to make. Second, in keeping the scene, Kovacs offered his most direct statement about the meaning of the play and his interpretation of the characters Agamemnon, Klytemnestra, and Iphigenia. Kayla Reinhard’s Messenger reflected the enthusiasm of someone moved by a mystical experience, while Kevin Price’s Agamemnon projected a man driven by coldblooded Realpolitik. But for me, the most powerful image in the Toronto production was the creation of the final stage picture. As Agamemnon departed, the soldiers took down and packed up the large white tent. The Chorus hesitated a moment to take in all that had come to pass, but then they too exited. Jocelyn Ruano’s Klytemnestra was left alone on stage, in tears and angry, clutching herself and boiling with rage. She knew that Agamemnon had fabricated this mythic rescue, a shameless attempt to cover his lie, pacify his wife, and try to buy himself a good conscience in the bargain. This was the moment when Klytemnestra’s resentment began.

DirectionGeorge Kovacs offered his audience an excellent Iphigenia in Aulis. He approached the play as an expert philologist and as a skilled homme de théâtre. As a philologist, he offered a provocative reading of the play, including parts of the text that some consider spurious. The result shows that the received text works in production and renders a cohesive narrative: audiences listened to the delayed prologue more carefully after first meeting the Servant and Agamemnon; the showy entrance of Klytemnestra and Iphigenia provided visual interest a third of the way through the play; and the reported rescue of Iphigenia and its reception by Klytemnestra left no doubt as to Agamemnon’s culpability in the murder of his child to advance his career. Fittingly, Kovacs’s work as a philologist informed his work as a theater artist who has a keen sense for creating powerful stage pictures. A sparse yet colorful set design, paired with colorful Greek costumes, supported the blocking. The only aspect of the production that seemed less than successful was the music. At the start of the play, the music was too North American and too modern; then it disappeared altogether. But this criticism itself seems out of place in a production that was on the whole tight and well-conceived. Most importantly, Kovacs directed his young cast to speak clearly and emotionally and to move believably through the action of a complex and problematic play.

ConclusionWith this production of Iphigenia in Aulis, The Classics Drama Group has added another Euripidean play to its list of accomplishments, enhancing its reputation for presenting Euripides’ plays in North America. IA ought to be seen more: it is an important play that offers the mature Euripides’ view of the prologue to the Trojan War and his reevaluation of characters well-known from Homer and earlier tragedy. The text affords actors some challenging roles and makes for exciting and intellectually stimulating theater. The CDG provided the opportunity to see this remarkable play and gave an outstanding performance.

notes

1 Aristotle, Poetics, 1453a29-30.

2 Goldhill, Simon, How to Stage Greek Tragedy Today (Chicago, 2007), 162.

3 Walker, Charles R., "Introduction to Iphigenia in Aulis," in Euripides IV (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1958), 211.

4 Roche, Paul, Euripides: Ten Plays (New York: Signet, 1998), xviii.

5 Blondell, Ruby, Mary-Kay Gamel, Nancy S. Rabinowitz, and Bella Zweig, translators and editors, Women on the Edge: Four Plays by Euripides (New York: Routledge, 1999), 327.

6 Dylan Morningstar was also cast as one of the soldiers but did not appear in the Toronto production.

7 Gamel (451n3) comments on the unusual opening of the play and directs the reader to basic scholarship on the problems.

8 Gamel's translation (335).

9 See for instance H. D. F. Kitto, Greek Tragedy: A Literary Study (New York: Routledge, 2011), 289.

10 Gamel's translation (344).

11 Poetics 1454a26-33.

11 Gamel (477n220) calls attention to the textual problems after line 1531.