Euripides’ ION

Directed by Rachel Herzog

April 2–4, 2015

Barnard/Columbia Ancient Drama Group

Minor Latham Playhouse

New York, New York

Reviewed by Talia Varonos-Pavlopoulos

The Nightingale-Bamford School

Since 1977 the students of the Barnard/Columbia Ancient Drama Group have been producing Ancient Greek and Roman plays in their original language, presenting students with a rare opportunity to temporarily resurrect a dead language and participate in the timeless process of storytelling while offering audiences the experience of seeing some of the greatest works of Ancient Western Drama in the original. Every year since the birth of this Barnard tradition, directors and actors have faced the unique challenge of performing these plays, far removed from their original chronological, cultural, and geographical contexts, in the original language, while still telling a story that is meaningful to a modern audience. This year’s production of Euripides’ Ion, directed by Rachel Herzog (Barnard College ’15), overcomes this challenge by infusing the ancient with the modern and, like Euripides himself, succeeds in reshaping and retelling a myth from a fresh perspective.

Euripides’ Ion, often characterized as a tragicomedy because of its comic moments and happy ending, tells the story of the reunion of the Athenian queen Creusa with her son, Ion. The tragedy explores the trauma of rape, memory, and the effects of divine actions on mortals. Taking the standard story of the rape and impregnation of Creusa by Apollo, Euripides focuses the narrative on Creusa1 by telling the story through her voice and from her perspective.2 The memory of the rape and the child that Creusa believes she left for dead haunts her and, while left hidden, binds her in a repetitive loop. Thus, by having Creusa tell her story – no fewer than four times during the play – Euripides not only exposes the trauma she has suffered and the human cost of Apollo’s assault, but also presents the process of remembering and the action of storytelling as a process of rehabilitation.

In the Barnard/Columbia Ancient Drama Group’s production of the Ion, the focus of the play was trauma and repetition. The issue and consequences of trauma were brought to life through the personae of Creusa, Ion, and the chorus, while the theme of repetition was present in almost every aspect of the play – choreography, music, and staging. The repetitive sequences in the music, the repetitively looped choreography, and the fusion of modern and ancient elements all functioned to remind us not only of the repetitive nature of memory but also that the very act of performing a play or relaying a story or even narrating a memory is a form of repetition and that, with each telling, the play, the story and the memory change.

The set design was minimal. The stage was subtly whitewashed. Chairs, two of white metal and four of dark wood, were arranged in a variety of configurations throughout the performance, defining the shape of the stage and how the actors interacted with the space, and they were used by the chorus as they witnessed the action of the play. A large, glossy, wooden chest, representing the altar and divinity of Apollo, was downstage right, and the musicians (Samuel Humphreys, composer and piano, and Isadora Ruyter-Harcourt, violin) occupied the opposite corner, downstage left. While the white bareness of the stage could have set a sterile, monochrome tone, it worked brilliantly with the lighting (Elizabeth Schweitzer, Barnard College ’18), which was as colorful and expressive as an artist’s palette, chromatically reflecting a theme or mood in the script and music.

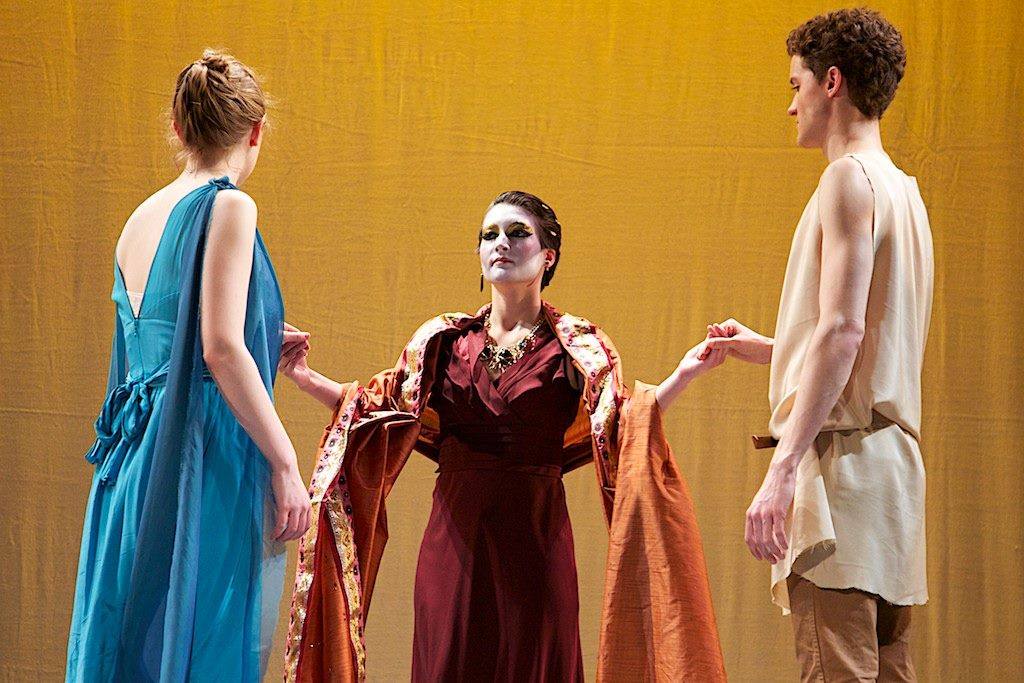

The play began with Hermes (Eli Aizikowitz, Columbia University GS ’17) in hot pursuit of the dance soloist from the chorus (Chloe Hawkey, Barnard College ’16). They ran through and around a clump of chairs and, with harmonious synchrony, leapt and turned in the air. Hawkey fell, her body spilling onto the stage before the chest, and Aizikowitz landed on his feet next to her. He arranged himself in a chair and watched as she repeated the fall. It was only after Hawkey had taken her place in a corner that Aizikowitz took the stage and began the prologue. [Image 1] Expertly straddling the generic divide of tragedy and comedy, Aizikowitz alternated between pathos and humor, bending the Greek to his will. His hand trembled as he describes Creusa abandoning the new-born Ion in the cave, he impishly sprang onto the chest to ventriloquize Apollo’s request that he deliver the baby to his temple in Delphi, and he playfully mimicked Ion piously sweeping when he announces the young man’s entrance. [Image 2]

In scene one, Ion (Caleb Simone, Columbia University, GSAS) entered the stage barefoot, singing a monody, a standard element of Euripidean tragedy. Although almost every play of Euripides features a monody or a duet between actors, such passages are usually performed by female characters in a state of great emotional turmoil.3 Ion’s monody is one of only three instances in which male characters perform a monody in Euripides—the others are the barbarian king in Hecuba (1056–82) and the Phrygian eunuch in Orestes (1369–1502)—and in all three instances the male figures occupy a marginal social position or liminal place in the mythical world. By introducing Ion in this manner, Euripides not only underlines his liminal nature as the semi-divine, bastard son of Creusa and servant to Apollo but, with the help of music, he also presents the simple action of cleaning as dramatically interesting.

Rather than shying away from the challenge of staging the monody, Herzog took it on to admirable effect. The music, composed by Samuel Humphreys, adhered to the Greek meter and had a fittingly Apollonian tone. Simone tunefully described his surroundings and daily custodial duties, and he praised the god in perhaps one of the stage’s first cleaning songs. On the one hand, Herzog’s staging and Simone’s execution of the song functioned to present Ion’s task of caring for Apollo’s temple as an act of devotion, worship and deepest reverence, thus elevating it from the quotidian to the ritualistic. On the other hand, it also cleverly acknowledged other characters of the stage and screen who sing and whistle while they work, particularly at the moment when Simone paused from his sweeping at the top of a crescendo and, with arms spread in a welcoming, round arc, raised his face and voice to the sun. [Image 3]

After Simone’s exit, Hawkey led the rest of the chorus (Anna Conser, Columbia Univeristy GSAS, Elizabeth McNamara, High School Student, Lina Nania, Hunter College ’15, Nathan Levine, Columbia College ’17, and Verity Walsh, Columbia College ’15) onto the stage in the parodos. They were costumed in cobalt skirts and corduroy pants with pleats that recall fluted columns, simultaneously underlining their integral role in the architecture of tragedy and its origins in choral dance. Singing in unison, the chorus marveled at the wonders of Delphi. Herzog’s decision to have the chorus sing in unison, rather than simply chanting or singing individually, was a brave one. The chorus is one of the most challenging elements of Greek tragedy to direct and perform, and despite its lack of the ancient chorus’s months of intensive training in song and dance,4 Herzog’s chorus expressively moved and sang as one, vividly reflecting the mood and emotion of the odes. Its effectiveness was especially pronounced in stasimon three, in which, praying for the success of their mistress’s plan, the chorus moved from sinister swirling of their fingers in poison to joyful, whirling dancing, and, finally, to the rejection and condemnation of Apollo’s treatment of Creusa and Ion. [Image 4, Image 5, and Image 6]

In scene two, Xuthos (Yujhán Claros, Columbia University GSAS) returned from the oracle and tirelessly tried to convince Ion that he is his father in what became a comic recognition scene and an easy audience favorite. Claros’s Xuthos was so overwhelmed at having his long-lost wish to become a father fulfilled that he unquestioningly and immediately accepted the fact, declared it to Ion, and bestowed his paternal affection on the young man. Simone, skeptical and concerned about the stranger’s behavior, loudly threatened to shoot him. In a moment of comic melodrama, Claros falls to his knees and, spreading his arms wide to expose his vulnerable chest, responded with genuine paternal pathos, κτεῖνε καὶ πίμπρη: πατρὸς γάρ, ἢν κτάνῃς, ἔσῃ φονεύς, “kill me but if you do, you will be the murderer of your father”. [Image 7] After Simone finally conceded, the scene continued with an investigation into the identity of Ion’s mother. The dialogue that followed between Xuthos and Ion was the comic gem of the play, containing Claros’s sheepishly legato yet matter-of-fact narration of the fateful night of delightful Bacchic worship, Βακχίου πρὸς ἡδοναῖς, that led him to the bed of a maenad.

As light-hearted and humorous as the father-son recognition may have been, scene three was heart-wrenching. Creusa (Elizabeth Heintges, Columbia University GSAS) entered the scene with a faithful, old servant (Vikram Kumar, Columbia College ’15) who had accompanied her to Delphi. Kumar’s aged servant had all the hallmarks of an old man—cantankerous voice, worry lines, and uncertain step—while Heintges’s Creusa was beautiful in her hopefulness for a child that would be the salvation not only of her line but also of her personal tragedy. They entered the stage clasping arms, eager to learn of the oracle Xuthos received from Apollo. A chorus woman (McNamara), aware of what the oracle had foretold, informed Creusa that she would never have children of her own and that Apollo had given Ion to Xuthos, to be his son. Heintges masterfully expressed Creusa’s overwhelming grief, speaking over and through the conversation between Kumar and McNamara. [Image 8] Inconsolable and with nothing else left to lose, Creusa recounted the story of her rape in the second lyric monody of the play, a medium that allowed her to express a range of emotions and communicate the violence, trauma, guilt and shame she has experienced. [Image 9] Heintges sang beautifully while the music, with its worrying tempo and the hurrying undercurrent of the violin, created an atmosphere of anxious dread. Kneeling next to the wooden chest representing Apollo’s altar, Heintges drew tears of shock and empathy by describing herself calling for her mother during the rape. She did not merely sing ὦ μáτερ (“O mother!”) but shrieked it, bringing that moment of hurt and helplessness to the present and making the scream, once lost in the depths of the cave, audible for the first time.

In scene four the chorus arranged their chairs into a semicircle, creating a space that recalled a circular orchestra and the choral dancing in stasimon three. Τhe messenger (Kay Gabriel, Princeton GSAS), one of Creusa’s maidservants, entered arrayed in a glossy, inky-blue dress, with a film of beige draped over and around her. Gabriel’s costume echoed those of the chorus, marking her as another indispensable element of tragedy. In an exquisitely descriptive rendering of the Greek, Gabriel’s messenger relayed the setting of the banquet in a detailed lento and the events that led to the discovery of the crime in a vivid allegro. [Image 10] One of the most moving parts of the speech occured when Gabriel described the dove that drank the poisoned wine from Ion’s cup. On bent knee, she cupped her hands and tilted her head back to mimic the doves drinking the wine and then crumpled onto the stage.

Scene five opened with urgency and panic. Heintges entered pursued by Ion, and the stage turned a painful yellow. In a panic, one of the chorus women (Walsh) led her to take refuge at the altar of Apollo, as Simone, transformed from the young man unwilling to kill even a bird into a man seeking blood and revenge, entered screaming and hurling chairs in his wake. Catastrophe, however, was prevented by the arrival of the prophetess (Simone Oppen, Columbia University GSAS). Oppen’s prophetess was a liminal figure, bridging the divide between human and divine and, as a result, not truly belonging to either world. Her voice was ethereal, metrical, and soothing, almost as if she were prophesying rather than merely speaking. After staying Ion’s rage and presenting him with the basket in which she had found him [Image 11], Oppen exited. She slowly but determinedly walked backwards to have one last long look before turning away, visually communicating the pain and longing that she cannot express in words.

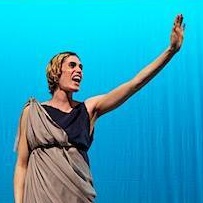

The recognition scene that follows was truly heartwarming. [Image 12] Glowing light cast mother and son in golden hues as Heintges and Simone sat on the floor in a filial embrace and joined their voices in song, rejoicing in their reunion. [Image 13] But the joy and delight was drained from Heintges face when, mirroring the scene with Xuthos, Ion asked about his father. Still singing, now with pleading urgency, she begged to be allowed to tell him later, but finally explained, cloaking the horror of her rape in music. Although Ion pitied his mother for her pain, he questioned the veracity of her story. The blinding epiphany of Athena (Victoria Schimdt-Scheuber, CU GSAS), the deus ex machina, brought Ion’s doubts and the play to an end. Accompanied by Aizikowitz, Schimdt-Scheuber entered the theatre though the main doors, which were flung open for her thundering, luminous entrance. In a fittingly austere and condescending tone, Schimdt-Scheuber congratulated Apollo on how well he had brought all these things to pass and directed Creusa not to spread the story of her rape if she wished her son to prosper. [Image 14] The play ended with Hawkey repeating the fall she had at the beginning of the play, but this time only once. As she lay on the stage, she hesitatingly looked up at Aizikowitz, who opened the lid of the chest, directing her to climb in. Hawkey complied and the lights fell just as the lid closed, confining and immobilizing the female figure, silencing the story, and ending the play.

Herzog ended the play with ambiguity, with a discreet question mark rather than a full stop. Hawkey’s fall at the end could not help but loop the audience back to the beginning and raise the question of whether the play would re-start if she ever escaped from the chest and even delicately alludes to the fact that what we had just witnessed was indeed a re-start, a re-play, a repetition.

The Barnard/Columbia Drama Group presented a provocative and meaningful production of Euripides’ Ion, which both entertained and intellectually engaged its audience. Not unlike Euripides’ original, this production of the Ion was conscious of its role in the creation of myth and art while being aware that the past cannot be abandoned or ignored in the present. In presenting the story of Ion, the members of the Barnard/Columbia Drama Group relayed the story of Creusa and Ion and, by emphasizing the theme of repetition, revealed that the very nature of story-telling, play writing, and performing is a reiteration of the past.

notes

1 As noted by Herzog in her director’s note, stories of the rape of mortal women by gods abound—even Ion points to their frequency in his sermon to Apollo (Ion: 442-447). But little thought is given to these women apart from the births of the semi-divine offspring.

2 It is important to underline that while “no female voice has survived to give us a hint of her experience in her own words . . . the portraits of women in drama may have reflected real social and historical issues, even if in a somewhat indirect fashion” (Fantham et al. Women in the Classical World: Image and Text. New York: Oxford University Press 1994: 70).

3 Storey, Ian and Arlene Allan. A Guide to Ancient Greek Drama. Malden: Blackwell Publishing: 2005.

4 Taplin, Oliver. Greek Tragedy in Action. London: Routledge: 1978, 2003.